The Story Board Blog

This blog is where announcements about story submissions will be made. Other blog posts will help you figure out how to write an awesome Adventure Game!

New blog post: What’s the Word?

What’s the Word?: Using Verbs to Make Better Flow Points

Written by Milo Duclayan 5/2024

Imagine you’ve just written your first adventure game. The world is awesome, the characters are unique, the lists are gorgeous, and the flow is… well, the flow is written, to some extent. You know what you want the story to look like and some major plot points, sure, but there’s a problem: the gameplay is just not engaging.

Gameplay and story are two very different things. The story is like a bird’s eye view of the entire game: it covers the themes and the aesthetic and the mission statement, as well as the plot at large. The gameplay is on the ground: the things that the players are actually experiencing and doing from moment to moment – the individual flow points. If the story is like looking at a forest, the gameplay is looking at each tree and seeing how it aligns with the rest.

Gameplay and story are two very different things. The story is like a bird’s eye view of the entire game: it covers the themes and the aesthetic and the mission statement, as well as the plot at large. The gameplay is on the ground: the things that the players are actually experiencing and doing from moment to moment – the individual flow points. If the story is like looking at a forest, the gameplay is looking at each tree and seeing how it aligns with the rest.

So, your story is good, but your gameplay is struggling. You have your flow structure (see “Flows for Algernon” elsewhere on the blog for more details), but you’re struggling to make the flow points themselves interesting enough. My solution? Verbs.

This article is going to cover two things: what verbs are (in game design) and why they’re a useful framing device for your flow points, and a quick exercise that you can use to practice with verbs and get more creative with your flow.

First, what the heck is a Verb?

The verb of a flow point is the main action that player characters will be engaging with. Every flow point needs a verb, and most flow points already have them, even if you haven’t noticed it.

Here’s a quick example flow point: The PCs battle through a horde of angry skeletons.

The verb here is actually already in the sentence: “Battle”. “Battle”, “Fight”, and “Kill” (and other verbs along those lines) are some of the most common verbs in adventure games. Other common verbs are things like “Fetch/Collect/Retrieve/Get” or “Talk/Listen/Learn”.

Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with those verbs. They’re common for a reason. But because they’re so common, it’s very easy to end up with a game full of them, and a game full of the same verbs gets repetitive fast.

The Exercise – Verbing your Flow

Here’s the exercise. This won’t give you a perfect flow point, but it’ll really help you kickstart your brain into thinking differently about how they tick in a helpful way.

Head to google and find yourself a Random Verb Generator. Try not to have any story in mind when you start this exercise, just be open to all possibilities. When you’re ready, roll yourself a random verb.

Now, take no more than 10 minutes, and make a flow point that uses that verb as its core action. I’ll do one alongside you so you can have some reference. Here’s the verb I’ve rolled: “Heat”.

When you roll for random verbs, you will get some very weird ones. At first it might be hard for you to imagine how you could make them into a flow point, but that’s why we’re doing this. The more you find ways to fit weird verbs into flow points in practice, the more unique and engaging your real flows will start to become. The easiest way I’ve found to start building a flow point is to define some or all of its five W’s (and H): Who, What, When, Where, Why (and How).

So, I need to make a flow point around the verb “Heat”. I can start by thinking about what they might be heating – let’s go with a furnace for an engine. Next I need to decide how they go about doing that action – maybe they have to take turns pumping a set of bellows. Lastly, the consequence – why the players are doing this flow point – if they don’t keep heating this engine, their friends inside the building will freeze. I’m missing the Who, When, and Where, but I think this is enough to give myself a solid idea of the flow point.

Done! Alright. Is this a good flow point for a game? Probably not. But it doesn’t have to be. The goal of this exercise isn’t to make perfect flow points – it’s to get you comfortable with using unusual actions, and finding more creative ways for your players to play your game (and also teach you some new verbs! You never know when a verb might come in handy). You can translate this skill into your real games, too.

Making verbs work for your game – Foundations

The reason this is an exercise and not something you can use for every adventure game is that some verbs just aren’t good fits. We write games for our players, so when we come up with the verbs that we’re actually going to use for our game, there are a few extra things we need to consider. These can be broken down into three main categories: empowerment, diversity, and mission. The first two are more foundational so we’ll do those first, and we’ll get to mission a bit later.

The reason this is an exercise and not something you can use for every adventure game is that some verbs just aren’t good fits. We write games for our players, so when we come up with the verbs that we’re actually going to use for our game, there are a few extra things we need to consider. These can be broken down into three main categories: empowerment, diversity, and mission. The first two are more foundational so we’ll do those first, and we’ll get to mission a bit later.

Empowerment is something that we often talk about in a vague way, but using verbs to define our flow points can make things much clearer. Empowerment is all about choosing engaging verbs, things that will give our players strong, active emotions. Active is an important word here, because verbs that let the players be active participants will almost always make for stronger flow points than passive verbs. Listen is a much less engaging verb than Talk. This is often the make-or-break for beginning game writers, and it’s one of the first things we look for when picking games to run for the summer. If your game is full of inactive verbs, you are relying on the players to make their own fun – and while they certainly can and will, it’s always better for them to have an engaging game to build on.

In addition to being active, your verbs should also be chosen with intent. While verbs like “Fight” and “Talk” are useful, they’re often used as a backup for when a writer isn’t sure what they want out of a flow point. When you decide what verbs you’re going to use for a scene, try to keep in mind the actual goals of that scene, not just in terms of the story and plot, but in terms of what emotions and challenges you want the players to experience. If that happens to be a fight, great – but choose all of your verbs with intent, and the players will feel it.

Diversity of verbs is another key thing you need to consider when you’re making the verbs for your game. Diverse games have two main things: wide ranges of verbs across the entire experience, and original verbs to create unique experiences. A diverse game will feel completely different to the players than any other game they’ve played, and will keep them engaged all the way through.

When considering the diversity of verbs in a game, the top priority is to make sure that your game as a whole has a wide range of verbs. This is another one of those key issues for early writers, but the reasoning is pretty simple: having flow points with different types of verbs available at the same time during your game will give everyone a chance to do something that they’ll enjoy. A game shouldn’t be all fight and fight-related verbs, because some players just don’t like fighting. A lack of diversity of flow points can often be hard to recognize when you’re writing a game without guidance, but being able to condense the experience of each flow point down to a verb makes it much easier to recognize and resolve.

After you’ve built a diverse foundation of verbs across the entire game, there’s the more advanced problem of common verbs. Your PCs have likely played tons of games filled with verbs like “fight”, “get”, or “talk”. It’s fine to have some of these verbs, and it’s often necessary to have some or all of them in some parts of your flow. Once you’ve learned the foundations, though, being able to find creative and unique verbs for your flow points can really help elevate your game to a whole new level. These flow points tend to be the most memorable, the things that people think about long after the game is over. That being said, creativity of verbs can’t come before the player experience. It won’t matter how unique your flow is if your players aren’t feeling empowered and engaged.

Making verbs work for your game – Putting it into Practice

In a game I ran back in 2022 called Tales of Anywhere, I had a series of flow points where the PCs needed to retrieve powerful relics from the gods of the world. While I could’ve just used the verb “Get” for all of those flow points, that would’ve meant having players do a really similar thing three times in a row. Instead, the verbs I used for those scenes were “Trick”, “Sneak”, and “Die”. These are all methods of achieving the same thing, but the core action is entirely different and way more engaging. In the “Trick” scene, the PCs went to a powerful god to get the artifact from them directly. This could have easily just used the verb “talk”, but remember, it’s always better to use active, intentional verbs when possible. Instead of just having a conversation and then giving the players the object, the players needed to actively trick the god into giving it to them, making it a much more empowering scene. Also notice that while the end goal is the same, each of these verbs is very different: “sneak” is more combat-oriented, “trick” is a social challenge, and “die” is a roleplay-heavy scene. Because of this, players have plenty of variety in the experiences they can choose from.

In a game I ran back in 2022 called Tales of Anywhere, I had a series of flow points where the PCs needed to retrieve powerful relics from the gods of the world. While I could’ve just used the verb “Get” for all of those flow points, that would’ve meant having players do a really similar thing three times in a row. Instead, the verbs I used for those scenes were “Trick”, “Sneak”, and “Die”. These are all methods of achieving the same thing, but the core action is entirely different and way more engaging. In the “Trick” scene, the PCs went to a powerful god to get the artifact from them directly. This could have easily just used the verb “talk”, but remember, it’s always better to use active, intentional verbs when possible. Instead of just having a conversation and then giving the players the object, the players needed to actively trick the god into giving it to them, making it a much more empowering scene. Also notice that while the end goal is the same, each of these verbs is very different: “sneak” is more combat-oriented, “trick” is a social challenge, and “die” is a roleplay-heavy scene. Because of this, players have plenty of variety in the experiences they can choose from.

Here’s another one: in Jay Dragon’s 2016 game The Horned King, there were a series of boss battles – it would be really easy to call these “fights”, but again, that would be exhausting to do over and over again. Instead, each boss battle had a different verb that made them feel really unique – Chase, Defend, Survive, Deceive, etc. This made the entire game feel incredibly dynamic, while still getting to keep the ‘boss rush’ style of flow.

The Mission Statement is something that Jay talked about in their article Drawn with Courage, which you can find earlier on the Story Board blog. At its core, the mission statements are like the overarching verbs of the entire game. In that article, referencing The Horned King, Jay uses the mission statements “Participating in the Ritual, Preparing Tactics and Executing Them, Feeling Unsure and Betrayed, and Fearing the Horned King” to describe the game’s core actions. Each of the verbs you choose for your flow points should support one (or better, multiple) of your mission statements. If your game is about glorious combat, choose verbs for your flow points that are powerful and combative. If your game is about dying in the darkness, choose verbs about running, hiding, and sacrificing. This won’t be the thing that makes a game unable to run, but making sure all of your verbs align with your mission can really help push the cohesion of the game to a new level.

Connecting verbs to your mission statement is also a great time to make use of unique game systems and mechanics. If you have a verb you plan to use often in your flow but you don’t think there’s a way to do it with the standard Wayfinder magic system, you can make one of your own. In Tales of Anywhere, I wanted “forgetting” to be a core verb of the game. There’s no memory mechanic in the Wayfinder magic system, so I made my own – for each second a certain monster was touching you, you’d forget a year of your life. Then I tied this mechanic into a bunch of my flow points where I wanted “forgetting” to be the verb. Just remember not to make too many new mechanics or you risk diluting your theme, or worse, ending up with a bunch of confused players.

Here’s a little bonus trick to wrap things up: you can do this exercise in reverse, too! Take any set of flow points that you’ve already written, and take a minute to try and break down what the core verbs of those flow points are. This can help you get a better idea of what your own game will actually look and feel like from the ground. It can also help you see where you’re starting to fall into the traps I mentioned above, like if you have a bunch of “fight” flow points in a row, or too few unique verbs, or your verbs just aren’t active enough.

If you look at a flow point and you can’t actually find any core verb for the PCs, that’s something to fix too – chances are you accidentally focused too hard on what’s happening with the SPCs or overall plot, and the actual actions of the players slipped away.

Conclusion

Verbs are an incredibly useful tool to have in your toolbox, and they’re big all over the world of game design for a very good reason. Even if you never end up using the exercise or breaking down your previous flow points, understanding that the core of your game is player action can help you hone in on what will make your game genuinely fun to play. The point of verbs is to remember that the game, at its core, is all about what the players are doing – you can make the most beautiful sets and the best story ever, but at the end of the day, the players will experience what they do above all else.

Verbs are an incredibly useful tool to have in your toolbox, and they’re big all over the world of game design for a very good reason. Even if you never end up using the exercise or breaking down your previous flow points, understanding that the core of your game is player action can help you hone in on what will make your game genuinely fun to play. The point of verbs is to remember that the game, at its core, is all about what the players are doing – you can make the most beautiful sets and the best story ever, but at the end of the day, the players will experience what they do above all else.

For me, there are two key takeaways from these exercises with verbs. First, you need to make sure that your verb foundations are solid before you start getting fancy with it – lock down your active verbs and make sure your game has a wide range of action types before you start messing with anything else. Second, when you are ready to start getting funky with your verbs, have fun with it! Trust your instincts, and let your creativity flow. Believe me, your game will thank you for it.

Written by Milo Duclayan 5/2024

Steering Made Clear

Steering Made Clear:

Play Style and its Theory

We play Adventure Games because we want a specific experience. We want to cry, we want to laugh, we want to look cool, we want to hit stuff with foam sticks. From filling out a character survey to the final moments of game, you as a player are tailoring your character and your portrayal of them to achieve these ends. This tailoring is often called steering- you steer your character’s actions to suit what you want to get out of the game. Steering is pretty intuitive to most players, it’s more defined terminology to say that you, the player, are in control of your character. (This is the sort of revolutionary idea you come across reading larp theory.) What’s helpful about recognizing that steering exists is that it makes you more likely to use it to your advantage, and better optimize your character’s actions to get what you want. Recently we’ve been talking about making out-of-game goals alongside character creation. Steering is the tool you use to achieve those goals.

We play Adventure Games because we want a specific experience. We want to cry, we want to laugh, we want to look cool, we want to hit stuff with foam sticks. From filling out a character survey to the final moments of game, you as a player are tailoring your character and your portrayal of them to achieve these ends. This tailoring is often called steering- you steer your character’s actions to suit what you want to get out of the game. Steering is pretty intuitive to most players, it’s more defined terminology to say that you, the player, are in control of your character. (This is the sort of revolutionary idea you come across reading larp theory.) What’s helpful about recognizing that steering exists is that it makes you more likely to use it to your advantage, and better optimize your character’s actions to get what you want. Recently we’ve been talking about making out-of-game goals alongside character creation. Steering is the tool you use to achieve those goals.

One particular type of steering I find interesting is playing to lose, which is also conveniently exactly what it sounds like. I’ve had a lot of great scenes come out of playing to lose, like two rounds of the Oldest Game that I played in Brennan Lee Mulligan’s Grad School, run during Winter Game 2017. Allowing my character, Puck, to lose the first game led to a quest to seek revenge and win– only to lose another round of the Oldest Game in an even more epic and disgraceful fashion. Books and movies are no fun if everything goes right for the protagonist. Playing to lose gives your character those speed-bumps an author would normally give to their characters, and often makes for a more interesting, cathartic story. Playing to lose can also be a great way to make your scene partner look good, which is one of the key rules of improv and always a good way to make a great scene.

One particular type of steering I find interesting is playing to lose, which is also conveniently exactly what it sounds like. I’ve had a lot of great scenes come out of playing to lose, like two rounds of the Oldest Game that I played in Brennan Lee Mulligan’s Grad School, run during Winter Game 2017. Allowing my character, Puck, to lose the first game led to a quest to seek revenge and win– only to lose another round of the Oldest Game in an even more epic and disgraceful fashion. Books and movies are no fun if everything goes right for the protagonist. Playing to lose gives your character those speed-bumps an author would normally give to their characters, and often makes for a more interesting, cathartic story. Playing to lose can also be a great way to make your scene partner look good, which is one of the key rules of improv and always a good way to make a great scene.

Steering is ultimately about achieving goals in game, and the Three Way model is one way to categorize how people achieve these goals. The Three Way model (a larp-specific adaptation of the Threefold model, which is used in general RPG theory) proposes that all play-styles fall loosely into three categories: gamist, dramatist, and immersionist. Gamist players play to win; they want to solve a riddle, they want to outsmart the villain, they want to stab the Big Bad even after it’s dead. Dramatist players are playing to tell a cool story, and often control their actions to fit into a traditional narrative with a nice satisfying ending. Immersionist players play because they want to be as true to the experience of their character and the world they’re playing in as possible- if their character would sit in a corner and cry, goddamnit they’re going to sit in that corner for as long as their character would.

Steering is ultimately about achieving goals in game, and the Three Way model is one way to categorize how people achieve these goals. The Three Way model (a larp-specific adaptation of the Threefold model, which is used in general RPG theory) proposes that all play-styles fall loosely into three categories: gamist, dramatist, and immersionist. Gamist players play to win; they want to solve a riddle, they want to outsmart the villain, they want to stab the Big Bad even after it’s dead. Dramatist players are playing to tell a cool story, and often control their actions to fit into a traditional narrative with a nice satisfying ending. Immersionist players play because they want to be as true to the experience of their character and the world they’re playing in as possible- if their character would sit in a corner and cry, goddamnit they’re going to sit in that corner for as long as their character would.

Of course these three play styles, like gender and dark chocolate, exist on a spectrum, and the boundaries can often be blurry. I myself fall somewhere between dramatism and immersionism. This is something I think shows in Puck’s actions; playing to lose both was definitely dramatist, but the desire to seek revenge was a result of deep immersion. Overlap is normal, and blending these different styles can often be unintentional. Someone accustomed to winning cool battles and finding loopholes in the magic system (typically a gamist perspective) when confronted with no fighting or magic can quickly become an adept narrative player, since the way to “win” that sort of scenario is to tell the coolest story. In a similar vein, playing for immersion can also get competitive, with some players bragging about bleed and overflowing emotions. These different type of players also often use the same mechanics. For example, steering can be used for both gamist and dramatist purposes, though is often frowned upon in cultures that put a high value on immersion. These elements can also easily co-exist in the same game, depending on whether there’s a tavern scene or a big battle or a mass ritual. It’s best to think of the distinctions of the Three Way model as ideas to play with rather than strict rules to follow. As the creator of the model, Petter Bøckmen, admitted, “Shoehorning everything into this model may lead to some really funny results.”

Of course these three play styles, like gender and dark chocolate, exist on a spectrum, and the boundaries can often be blurry. I myself fall somewhere between dramatism and immersionism. This is something I think shows in Puck’s actions; playing to lose both was definitely dramatist, but the desire to seek revenge was a result of deep immersion. Overlap is normal, and blending these different styles can often be unintentional. Someone accustomed to winning cool battles and finding loopholes in the magic system (typically a gamist perspective) when confronted with no fighting or magic can quickly become an adept narrative player, since the way to “win” that sort of scenario is to tell the coolest story. In a similar vein, playing for immersion can also get competitive, with some players bragging about bleed and overflowing emotions. These different type of players also often use the same mechanics. For example, steering can be used for both gamist and dramatist purposes, though is often frowned upon in cultures that put a high value on immersion. These elements can also easily co-exist in the same game, depending on whether there’s a tavern scene or a big battle or a mass ritual. It’s best to think of the distinctions of the Three Way model as ideas to play with rather than strict rules to follow. As the creator of the model, Petter Bøckmen, admitted, “Shoehorning everything into this model may lead to some really funny results.”

Playing style is ultimately up to the individual player, but some games are more suited towards one end of the spectrum than another, and game writers should consider these different styles when writing. The most obvious distinction is that Wayfinder intro games lean more towards gamism, while our advanced games are more conducive to immersionism, though this is certainly not exclusive, and any play-style could be implemented in any game. The Three Way model can be useful for a game writer in helping to define what they want out of their game and what the audience of the game is. Recognizing that they want players to win leads to creating very different scenes than wanting their players to feel immersed, and oftentimes these games attract different types of players.

Whether you were aware of all this theoretical jibber-jabber before or not, you have already used your intuition as a player to tailor your play style to different scenarios. You wouldn’t play a comedy game with the high dramatic style you might use in a fantasy game, and you probably wouldn’t put on a Texan accent in a fae court. The ideas behind steering and the Three Way Model are all similar ways to change how you play. They’re not set in stone, and one is certainly not better than the other, just different. What my hope is, with this knowledge in hand, you will try something new in the next game you play, and maybe learn more about yourself and this delightful artform we all create together.

Whether you were aware of all this theoretical jibber-jabber before or not, you have already used your intuition as a player to tailor your play style to different scenarios. You wouldn’t play a comedy game with the high dramatic style you might use in a fantasy game, and you probably wouldn’t put on a Texan accent in a fae court. The ideas behind steering and the Three Way Model are all similar ways to change how you play. They’re not set in stone, and one is certainly not better than the other, just different. What my hope is, with this knowledge in hand, you will try something new in the next game you play, and maybe learn more about yourself and this delightful artform we all create together.

FURTHER READING:

The original proposal of the Three Way Model by Petter Bøckman, from the 2003 Knudepunkt book, As Larp Grows Up.

An article from the 2018 Knutpunkt book, Playing the Cards, about some further dramatist concepts and how to incorporate them into large-scale larps.

The Manifesto of the Turku School, which contributed to the overwhelming prevalence of immersionism in Nordic larp. While it does have some flaws and make some polemic statements (most hysterically in reference to sacrificing designer’s work “to the unholy altar of social relations”), it’s essential in understanding the history of larp.

Written by Julian Schauffler

4/10/18

Three Ways to Cut Cake

Three Ways to Cut a Cake:

Game Mechanics Part 1

Game Mechanics are one of the most complicated aspects of writing an Adventure Game, and it’s not because of the difficulty. Every single game has mechanical elements, with different degrees of prominence within a particular game. These mechanics develop together into systems – relationships of mechanics that inform each other. For example, each different spell a wizard can know is a mechanic, together they form a system. As someone who is involved heavily in the Tabletop Roleplaying Game world, a world where systems are far more prominent when discussing game design, I find myself thinking a lot about how to use mechanics and systems to develop the emotional reactions I would like in a game. In this article, I’m not going to talk about how to use game mechanics for your game. Not yet. Instead, I’m going to introduce a vocabulary for talking about game mechanics, taking them apart, and examining them critically. None of these systems of mechanical discussion are perfect for every game mechanic. Instead, you should mix and match these different divisions of game mechanics to gain a deeper understanding of how game mechanics work.

Game Mechanics are one of the most complicated aspects of writing an Adventure Game, and it’s not because of the difficulty. Every single game has mechanical elements, with different degrees of prominence within a particular game. These mechanics develop together into systems – relationships of mechanics that inform each other. For example, each different spell a wizard can know is a mechanic, together they form a system. As someone who is involved heavily in the Tabletop Roleplaying Game world, a world where systems are far more prominent when discussing game design, I find myself thinking a lot about how to use mechanics and systems to develop the emotional reactions I would like in a game. In this article, I’m not going to talk about how to use game mechanics for your game. Not yet. Instead, I’m going to introduce a vocabulary for talking about game mechanics, taking them apart, and examining them critically. None of these systems of mechanical discussion are perfect for every game mechanic. Instead, you should mix and match these different divisions of game mechanics to gain a deeper understanding of how game mechanics work.

What is a “Game Mechanic”?

At its most basic level, a game mechanic is a rule about how the world of your adventure game functions. Technically, every single aspect of how we interact with an adventure game is a game mechanic. We just take the majority of these “mechanics” for granted. For example, a core game mechanic that is true in 99% of all Adventure Games is how a sword operates. This is, in many ways, the heart of the greater Wayfinder system – the core that everything else is rooted in. On a more abstract level, something like “talking” is technically a game mechanic. When I speak out loud, it’s understood that my character is speaking out loud and saying the same words that I’m saying normally. However, we can appreciate this as a mechanic when we notice when this isn’t true. If I cross my fingers before I talk, this indicates at Wayfinder that I’m speaking out-of-character, and that my character isn’t actually saying the words that I’m saying at the moment. Similarly, words can indicate mechanical importance. If I point at you and yell “Knockdown!”, then it is left unclear whether my character is actually saying these words. Instead, it is understood that I am casting a spell or using psionic abilities to repel you and shove you onto the ground.

Game mechanics develop into a System. A System is a series of interconnected mechanics. The classic example is the Wayfinder Magic System. It is composed entirely of different moving parts, that intersect to form a cohesive whole. Systems make assumptions about how play is supposed to operate. By including swords in your game, you are probably assuming at least the following things:

- 1. Swords will exist in the game and at least the threat of sword use will appear.

- 2. That when a player sees the out-of-game object we refer to as a sword, they will understand that that object represents a large hunk of metal (they will imagine it is a sword).

- 3. That injury or death is possible within the game, and there are additional game mechanics to handle that.

That last point is the most important. Game mechanics naturally beget other game mechanics, as part of developing a system. We possess a death system, in which players understand what is to happen mechanically when they are killed as a result of actions in game. That is a game mechanic. As an extension of that, there must be game mechanics in place to facilitate what happens ways to die. Do I die if someone points at me and says “Death!”. Do I die if someone hits me with a sword or shoots me with a NERF bullet? Do I die if someone shines a red light on me? What if something weird happens, like I set off a tripwire? These are all game mechanics that combine with the mechanism of RE to create a game system.

That last point is the most important. Game mechanics naturally beget other game mechanics, as part of developing a system. We possess a death system, in which players understand what is to happen mechanically when they are killed as a result of actions in game. That is a game mechanic. As an extension of that, there must be game mechanics in place to facilitate what happens ways to die. Do I die if someone points at me and says “Death!”. Do I die if someone hits me with a sword or shoots me with a NERF bullet? Do I die if someone shines a red light on me? What if something weird happens, like I set off a tripwire? These are all game mechanics that combine with the mechanism of RE to create a game system.

Cues and You

New Game Mechanics can be challenging. An improperly implemented game mechanic can be at best confusing, or at worst actively destructive to the game. The key to creating a game mechanic which successfully adds to the game is ease of remembrance. The easiest way to do that is to build it into Wayfinder’s pre-existing system that is assumed in games. For example, the majority of spells at Wayfinder are communicated via pointing at someone and yelling one or two words that correspond to what the effect is for the player being pointed at. This is a fairly intuitive system – the receiving player is literally being instructed in how to react. If I want a new mechanic that represents the evil villain’s ability to rot away at people’s skin, the easiest way to do that and ensure people will remember it is by attaching a verbal cue – perhaps the villain points at its victim and yells “Wither!”. Wayfinder most often uses verbal cues in its game mechanics (although somatic cues – cues that are communicated via unusual physical action – aren’t uncommon, especially in the Sci-Fi system and its derivatives) However, that’s not always the appropriate solution. What if I want the withering effect to be constant?

In that scenario, a common solution is to tie the withering to a visual cue. I might, before game, inform everyone that if they see Jud Packard, that means their skin begins to rot off. Sometimes, this works! However, visual cues don’t often work passively. It’s easy to forget that there’s something special associated with Jud Packard, in the heat of the moment. The best way to ensure players remember visual cues is by making the visual cue impossible to miss and to really, really drill it into their heads. Silence Blooming, a game ran in 2017 by myself and Jeremy Gleick, made heavy use of visual cues for game mechanics. The one that really stuck in people’s heads was “Everyone follow the Whale Monster!” which is to say, that when people see a giant monster composed of multiple moving people, they have to follow it. We turned this into a callback to ensure that people would remember it, and it worked effectively in game. We also made strong use of colored lights for verbal cues. I was wrapped entirely in glowing string lights for game, and if you had a particular disease, you had to follow me. This only mattered to people with the disease, so people were already aware of something to look out for. Also, string lights are very visible at night.

In that scenario, a common solution is to tie the withering to a visual cue. I might, before game, inform everyone that if they see Jud Packard, that means their skin begins to rot off. Sometimes, this works! However, visual cues don’t often work passively. It’s easy to forget that there’s something special associated with Jud Packard, in the heat of the moment. The best way to ensure players remember visual cues is by making the visual cue impossible to miss and to really, really drill it into their heads. Silence Blooming, a game ran in 2017 by myself and Jeremy Gleick, made heavy use of visual cues for game mechanics. The one that really stuck in people’s heads was “Everyone follow the Whale Monster!” which is to say, that when people see a giant monster composed of multiple moving people, they have to follow it. We turned this into a callback to ensure that people would remember it, and it worked effectively in game. We also made strong use of colored lights for verbal cues. I was wrapped entirely in glowing string lights for game, and if you had a particular disease, you had to follow me. This only mattered to people with the disease, so people were already aware of something to look out for. Also, string lights are very visible at night.

Another tool you have at your disposal disconnects mechanics from active players. Object cues and written cues are both ways of allowing mechanics to exist in the world without having a player enforcing them. An object cue is a particular object with a mechanical effect when you interact with it – a sword hurts you when you’re hit by it, or a red LED light melts your skin off when it’s held up to you. Written cues instruct the player in how to proceed. A common one is “sickness papers”, when you have a small piece of paper that explains to you the symptom of a disease you possess. Sometimes, these cues blend together. An object might have a written cue on it, to instruct you as to what happens when you pick it up, and a piece of paper might represent an object – like a piece of tape with TRAP written on it.

Often, it’s possible for a single game mechanic to possess multiple cues attached to it at a single time. While a sword kills you if it hits you, it requires a somatic component (being swung at you) to actually have an impact – we have an understanding that a sword just sitting there won’t injure you. Spells like Repulsion also possess a somatic component – outstretched arms – and an object cue and a visual cue are closely interlinked. The important part for a mechanic within a system is that the mechanic is easy to remember and consistent with other mechanics, both within the game and in a larger context at Wayfinder. For example, it is commonly accepted that when you hear someone blow a vuvuzela, that means they are freezing time. This is such an ingrained reaction for many of us that even when told the vuvuzela blast means something else, we’ll often react by freezing. It often goes without saying, but you also want to have consistency within the world of the game – if red LED lights cause your skin to melt off, make sure Sets & Props isn’t using any for any scene if that’s not your desired effect!

Naturalistic vs. Symbolic

In Art History (my personal discipline) there is a continuum that exists, between naturalism (that is, art that perfectly resembles the real world) and symbolic (art that has no visual connection to the natural world). We can also construct this line for game mechanics. This section of this article draws on the work of Lauri Lukka in “6 Levels of Substitution: The Behavioral Substitution Model”, published in The Knudepunkt 2015 Companion Book. (An aside: if you ever have a free night or two, hunt down all the Knutpunkt/Knudepunkt/Solmukohta articles you can find, and check them out. There are some real gems!)

In Art History (my personal discipline) there is a continuum that exists, between naturalism (that is, art that perfectly resembles the real world) and symbolic (art that has no visual connection to the natural world). We can also construct this line for game mechanics. This section of this article draws on the work of Lauri Lukka in “6 Levels of Substitution: The Behavioral Substitution Model”, published in The Knudepunkt 2015 Companion Book. (An aside: if you ever have a free night or two, hunt down all the Knutpunkt/Knudepunkt/Solmukohta articles you can find, and check them out. There are some real gems!)

On one end of the spectrum, (no substitution, in Lukka’s language) is a game mechanic which is perfectly naturalistic. What the game mechanic represents as a symbol is exactly what happens in real life. An obvious example of this is that in the majority of game, “walking” as an in-game action is represented by performing the physical action “walking”, which is to say, when you want to walk around, you walk around. Another, significantly more dangerous example would be a game in which people actually stab each other with swords to represent a swordfight. Sometimes, a perfectly naturalistic game mechanic makes sense – we don’t need to abstract walking (the majority of the time). However, for other mechanics, it’s sometimes dangerous – there’s a reason we have foam swords.

The other end of that continuum is a perfectly symbolic (or abstract) game mechanic. This is when the symbol of the concept completely replaces any real interaction with the world. This could be a spirit journey where someone describes to you what’s going on, or where you read information off of a piece of paper on the ground. These are mechanics you’d expect to find in a tabletop game, or perhaps in play-by-post. Your physical body doesn’t matter, as it’s been completely substituted.

In the middle are game mechanics which either depend more heavily on naturalistic behavior, or on symbolic information. Our system for sword combat, where we have abstracted it to the point where we’re not using literal swords, and we treat the swords differently than how they are as actual objects, but we strive for realism in how the swords operate, is a mostly-naturalistic mechanic. A system in which, instead of fighting with swords, you engage in a dance party, is heavily abstracted but in an interesting way. It’s still satisfying the same physical mechanisms as a sword fight does, but the swords have been abstracted out of the combat. Even further abstracted would be a system where sword fights are represented through a game of poker. Gone is the physical association, and instead is a mental association. One could say that a game of Texas Hold’em is a lot like a Mexican Standoff in terms of the tenseness and cultural associations, making a symbolic switch like that appealing.

In the middle are game mechanics which either depend more heavily on naturalistic behavior, or on symbolic information. Our system for sword combat, where we have abstracted it to the point where we’re not using literal swords, and we treat the swords differently than how they are as actual objects, but we strive for realism in how the swords operate, is a mostly-naturalistic mechanic. A system in which, instead of fighting with swords, you engage in a dance party, is heavily abstracted but in an interesting way. It’s still satisfying the same physical mechanisms as a sword fight does, but the swords have been abstracted out of the combat. Even further abstracted would be a system where sword fights are represented through a game of poker. Gone is the physical association, and instead is a mental association. One could say that a game of Texas Hold’em is a lot like a Mexican Standoff in terms of the tenseness and cultural associations, making a symbolic switch like that appealing.

Lukka posits that this is connected to a “Dual Processing Model” and proposes a Grotesque Zone where the naturalistic and symbolic clash (an idea I disagree with for subtle reasons but is still a useful mechanism for discussion). I would argue that game mechanics anywhere along the line can be failing, but the advantage of the continuum is that it gives you the ability to understand how you want your mechanics to be realized, and when they fall apart, why they fall apart. It’s possible for a game mechanic to be more abstracted than it needs to be, by involving layers of thought that replace one’s ability to intuit how the mechanic works. Conversely, it’s possible for a game mechanic to be more naturalistic than it needs to be, either by endangering people or forcing you to conform to your weaknesses as a physical person. An example of how this can be contentious is the Hide mechanic used in the current Magic System. One camp of people argues that the mechanic is too abstracted, making people worse at hiding because it gets in the way of how to “actually” hide as a Rogue. The other camp argues that the mechanic is perfectly fine because it abstracts the act of hiding into something anyone is capable of doing and something they’re guaranteed to succeed at physically.

Game Mechanics as Improv Prompts

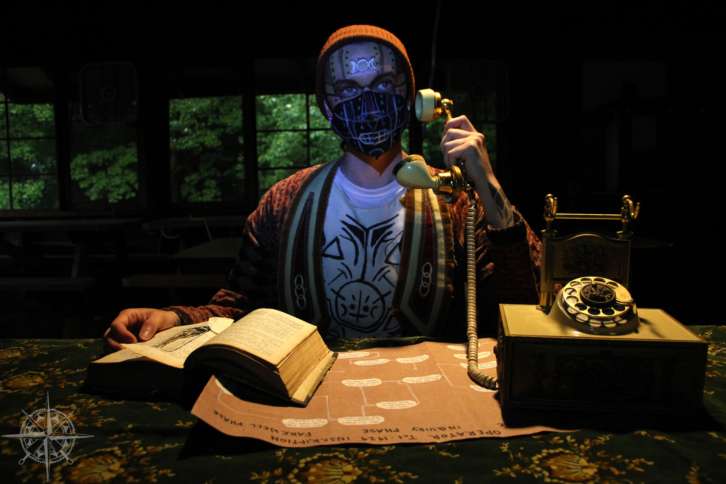

![]() A third and valuable way of subdividing game mechanics is by how players engage with them. There are four such categories in this sense – Active Mechanics, Passive Mechanics, Reactive Mechanics, and Collaborative Mechanics.

A third and valuable way of subdividing game mechanics is by how players engage with them. There are four such categories in this sense – Active Mechanics, Passive Mechanics, Reactive Mechanics, and Collaborative Mechanics.

Active mechanics are ones that are forced upon a player by another player or their environment. If I hit you with a sword, I have now caused you to experience a scene against your will. You didn’t choose to be hit by a sword (maybe), but you are now given the improvisational prompt “you’re wounded!”. Similarly, if I point at you and yell, “Fear!”, I’m directly giving you a prompt to change how you’re roleplaying. Sometimes, Active mechanics will require me to change my own behavior – a spell might physically exhaust me, for instance – but I’m the one making the choice to invoke the convention.

Passive mechanics are internal ones. They’re truths about one’s character that define how that character operates. Often, no one knows a particular passive mechanic exists, or it folds effortlessly into pre-existing systems. A curse that’s built into my character from the start of game is an example of a passive mechanic – if I do something, I must change my roleplaying, but no one needs to know about that but me. Another passive mechanic is the ability to hide, or the entire mechanic for reincarnation and death. Passive mechanics aren’t put upon you, except by either the gamewriter or yourself.

Reactive mechanics occur reflexively when another player does something, but otherwise have no effect. The best example of a reactive mechanic is Protection. Reactive mechanics tend to be very similar to passive mechanics, as you’re the only person who needs to keep track of them, but you tend to need to inform another player that they’re occuring. Personally, I’m not a big fan of reactive mechanics whose only function is to protect you from having to react to magic. The entire function of the system is to give people the chance to be affected by cool magic, and while it can be empowering to not have to react, it clashes against the interesting scene made by having to react.

Finally, collaborative mechanics are ones which two or more people opt into together, taking on the improv prompt as a group. The only example of this that I can think of in the traditional magic system is Sanctuary, where multiple people can be guarded by a single ringing bell, but it’s possible to create others. I believe collaborative mechanics are especially valuable in games when you want to foster a sense of community and team-building. In a sense, all rituals are collaborative mechanics, as they’re a group of people working together to execute the mechanic. Often, collaborative mechanics have someone orchestrating them, but the players are all joining into it to build the scene.

Examples of Evaluating Mechanics

For the final portion of this article, we’re going to take a few game mechanics, and you must identify the cues of the mechanic, whether the mechanic is more naturalistic or symbolic, and whether the mechanic is active, passive, reactive, or collaborative. In addition, each mechanic has a different flaw with it that will cause problems during game, and I’d like you to identify how this appears. This isn’t a test – I don’t expect you to guess them perfectly. Instead, I want you to start using these different division systems as a way of talking about mechanics, and understand how they can be applied, and how they can be useful. If you disagree with me on any of these mechanics, you’re welcome to hunt me down on the internet and passionately explain to me why I’m wrong.

For the final portion of this article, we’re going to take a few game mechanics, and you must identify the cues of the mechanic, whether the mechanic is more naturalistic or symbolic, and whether the mechanic is active, passive, reactive, or collaborative. In addition, each mechanic has a different flaw with it that will cause problems during game, and I’d like you to identify how this appears. This isn’t a test – I don’t expect you to guess them perfectly. Instead, I want you to start using these different division systems as a way of talking about mechanics, and understand how they can be applied, and how they can be useful. If you disagree with me on any of these mechanics, you’re welcome to hunt me down on the internet and passionately explain to me why I’m wrong.

- 1. The Sword of Angrathnar. If a glowing red sword would kill you, you become a ghost that follows the wielder of the blade around, invisible to everyone. The wielder can issue commands to you, which you must obey.

- 2. Rosie Ring. If two Spore Disciples hold hands together and start dancing while singing a terrifying nursery rhyme, they begin a ritual that transforms them into the host of an arcane disease that warps reality. They must dance for five minutes straight, at which point they may become horrible monstrosities, and change into monster costumes.

- 3. Misty Step. If a spell would be cast on a Wizard who is capable of casting the spell themselves, they may instead ignore the spell and wave their arms around, putting on their spirit costume. They may then run up to 30 feet and reappear somewhere else.

- 4. The Mark of Kaine. Those who carry the mark of Kaine, a black rune on one’s forehead, cannot be harmed by any wound, and instead any wound that would harm them appears on those who tried to harm them.

Answer Key

1. The Sword of Angrathnar. This is a visual object cue (the sword is an object, and it’s glowing red, which reminds you visually). This is not especially symbolic or naturalistic, as it abstracts a non-natural experience, but I could hear arguments leaning either way. It is an active game mechanic, as the wielder of the weapon inflicts it onto other players with the blade itself. The flaw that I would articulate is that the mechanic is too active – it takes control and limits the victim’s games in a way that isn’t fun (they now have to be ghosts forever, and don’t get to make their own choices while being invisible to everyone).

1. The Sword of Angrathnar. This is a visual object cue (the sword is an object, and it’s glowing red, which reminds you visually). This is not especially symbolic or naturalistic, as it abstracts a non-natural experience, but I could hear arguments leaning either way. It is an active game mechanic, as the wielder of the weapon inflicts it onto other players with the blade itself. The flaw that I would articulate is that the mechanic is too active – it takes control and limits the victim’s games in a way that isn’t fun (they now have to be ghosts forever, and don’t get to make their own choices while being invisible to everyone).

2. Rosie Ring. This is a somatic cue (dancing), accompanied by a verbal cue (singing). It is fairly naturalistic, as even though it represents a non-natural process, the process is very literal. You’re dancing and singing, which is what you’re doing in the fiction. At the end, there’s a split into abstraction as they have to stop and change into monster costumes. Finally, the mechanic is collaborative – it’s engaged willingly by two people, and alters their behavior without directly impacting anyone else. The flaw of this mechanic is that naturalism and symbolism are clashing. Having to stop the immersive scene at the end of it to change into costumes kills the mood, and ruins whatever the writer was trying to go with with the creepy transformation sequence.

3. Misty Step. This mechanic features a visual object cue (the spirit costume), and hypothetically a somatic cue (the waving-around arms). It is neither especially naturalistic or symbolic, to the point where it’s unclear what’s going on from either perspective. Finally, it is a reactive mechanic, which only allows you to do something if someone’s cast a spell on you. There’s two main problems with the spell: first, the somatic cue is unnecessary and confusing. The other problem is that it’s too reactive. You have to jump through too many hoops in order to use it, and there’s a good chance someone is let down by their spell randomly happening to fail.

4. The Mark of Kaine. This is a visual cue (the forehead symbol). It’s neither especially naturalistic or symbolic, beyond how our own weapon system is abstracted. Finally, the kind of prompt this is is tricky. On one hand, it’s active – you’re changing your roleplay behavior because of something the person with the mark is doing. On the other hand, it’s reactive – your own actions are causing something to happen to you. Perhaps from the person with the mark’s perspective, it’s passive. They don’t have to do a single thing. The problem with this mechanic is this lack of clarity in how the cues operate. When we use this mechanic normally in Wayfinder games (often called “Thorns”), we accompany it with a verbal cue (yelling “Thorns!” when the person with the mark is injured). This reminds the person engaging in the injuring how the mechanic works, and turns it into a reactive mechanic that causes an active mechanic to occur.

Conclusion

Game Mechanics are, on a fundamental level, how we interface with the fiction that is the Adventure Game. Every single thing you do in an adventure game is technically a game mechanic, and even something as simple as talking to someone else can have multiple meanings or purposes. Don’t treat your game mechanics like something extra, to toss on top of your game when you need some garnish. They’re the tools you use to immerse your players and build your narrative. Take command of your mechanics, and sculpt your world with them. In the future, I’ll be talking about how mechanics combine, and how that builds a system.

Game Mechanics are, on a fundamental level, how we interface with the fiction that is the Adventure Game. Every single thing you do in an adventure game is technically a game mechanic, and even something as simple as talking to someone else can have multiple meanings or purposes. Don’t treat your game mechanics like something extra, to toss on top of your game when you need some garnish. They’re the tools you use to immerse your players and build your narrative. Take command of your mechanics, and sculpt your world with them. In the future, I’ll be talking about how mechanics combine, and how that builds a system.

Written by Jay Dragon

March 30, 2018.

You Win Or You Die

You Win Or You Die:

Political Games and You

I’ll be completely honest – in my opinion, Game of Thrones is not a very good TV show. That doesn’t stop me from watching it (doing my best to avoid the constant misogyny and racism). The only actually enjoyable part of Game of Thrones is the political intrigue and power plays. Because boy are those a lot of fun! Watching people scheme against one another and forge (and break) powerful alliances in the name of their aspirations and deep-set character desires is great! Getting to be a mover and shaker in a situation like that one is an amazing example of meaningful choice – your actions have direct consequences for the entire world. Sometimes at Wayfinder we try to capture the experience of that situation in what we call “Political Games”. We’re not the only people to try that out – obviously other LARPs enjoy political settings, and you could easily argue that Model UN and Model Congress are perfect examples of political games (just without the roleplay). But, in my experience, it’s incredibly hard to write a good political game. In order to understand why, and how we can do better, we should take a look at what exactly a political game is and what it needs.

I’ll be completely honest – in my opinion, Game of Thrones is not a very good TV show. That doesn’t stop me from watching it (doing my best to avoid the constant misogyny and racism). The only actually enjoyable part of Game of Thrones is the political intrigue and power plays. Because boy are those a lot of fun! Watching people scheme against one another and forge (and break) powerful alliances in the name of their aspirations and deep-set character desires is great! Getting to be a mover and shaker in a situation like that one is an amazing example of meaningful choice – your actions have direct consequences for the entire world. Sometimes at Wayfinder we try to capture the experience of that situation in what we call “Political Games”. We’re not the only people to try that out – obviously other LARPs enjoy political settings, and you could easily argue that Model UN and Model Congress are perfect examples of political games (just without the roleplay). But, in my experience, it’s incredibly hard to write a good political game. In order to understand why, and how we can do better, we should take a look at what exactly a political game is and what it needs.

Tell me about it!

When I visualize a political game, I imagine something like the third game of Legendary Camp 2011. In it, representatives from across the known world gathered to petition the representatives of the gods in order to achieve their agendas and manipulate their future. There was a huge map with soldiers on it, political intrigue, assassination attempts, and drama. It determined the very fate of the world (which was the shared setting for the rest of the camp and for the Finale of that year). A small group of bureaucrats became dictators through careful use of council legislation, and silkworm farmers from the far north helped save the world. Now, a visualization is nice and all, but we can’t go around categorizing a game as political or not without some kind of definition. For the purposes of this article, I will define a political game as the following:

A game in which individuals or small groups have very direct goals (free your people from slavery, shut down your enemy’s factories, get your plan to save the world approved by the UN)

A game in which individuals or small groups have very direct goals (free your people from slavery, shut down your enemy’s factories, get your plan to save the world approved by the UN)

These goals cannot be achieved by action and quest-taking – they require social interaction, negotiation, and scheming. (You can’t save your people from the slavers without the permission of the Emperor)

There is no external enemy interrupting the negotiation process. People are free to argue in peace, and while there might be pressure from outside (negotiators hide in a bunker, etc.) ultimately, this doesn’t stop the arguments.

That’s cool, and simple too! However, you might be able to see some flaws in this structure. First and foremost, not everyone enjoys arguing. A lot of our players are here to fight with swords, have emotional moments, or, y’know, do things. If a game is purely political, with no room for anything else, it’s going to miss the mark for almost everyone. That’s a big problem. Also, another issue is that most people either lack the personal initiative or the in-character ability to make a ton of meaningful change. Anyone can swing a sword or cast a spell, but not everyone feels comfortable with public speaking or backroom deals. In any political game, there will be people with more status and charisma than others. If you lack both of those things, you’re not going to get much done. The final issue, which isn’t universally true but is overwhelmingly common, is that nothing actually means anything. In Game of Thrones, the characters care about the fate of Westeros because they’re the fools living there. In a political game, once the game is over, none of it mattered. There’s no rewards for becoming king (besides bragging rights) and no one is going to be blown away that you shut down your competitor’s factory. It’s really hard to become invested in something when it doesn’t really matter to you (even if it matters to your character).

Yikes! Those are some pretty tough hurdles to overcome. However, I love political games so much, that I want to find some solutions. So first off, I’m going to talk about what’s needed to make a good political game. Then, I’m going to talk about what you need for a great political game, that will get everyone involved.

What’s good?

The fundamentally most necessary thing for a political game is stuff. Information, secrets, rumors, factoids, legal documents, the whole nine yards. This creates an immersive environment, as people now have tools they can fall back on to prove their points and engage in intrigue. In most games, we enjoy being able to make things up as we go along (improv!) but in political games, it’s good to have a framework that gives people a solid benchmark for reality. It’s best if this stuff can have a physical form in game – people can’t hold all the information they need in their heads at once. Writing all of this stuff is a lot of work, however. If you’re comfortable with that (like me) you’ll do strong, but if you’re not, you’re going to need another solution. That’s okay! I bet you can come up with a lot of creative solutions that will all accomplish the same thing – giving people tools in game that they can use to feel like the setting around them is real and that their actions will have meaningful impact.

The fundamentally most necessary thing for a political game is stuff. Information, secrets, rumors, factoids, legal documents, the whole nine yards. This creates an immersive environment, as people now have tools they can fall back on to prove their points and engage in intrigue. In most games, we enjoy being able to make things up as we go along (improv!) but in political games, it’s good to have a framework that gives people a solid benchmark for reality. It’s best if this stuff can have a physical form in game – people can’t hold all the information they need in their heads at once. Writing all of this stuff is a lot of work, however. If you’re comfortable with that (like me) you’ll do strong, but if you’re not, you’re going to need another solution. That’s okay! I bet you can come up with a lot of creative solutions that will all accomplish the same thing – giving people tools in game that they can use to feel like the setting around them is real and that their actions will have meaningful impact.

Another good tool is to have a mediator, someone who can help keep game flowing smoothly. In most games, this role is filled by PC leaders. But in political games, PC leaders often have their own goals and intentions that run counter to being a good PC leader. For example, a PC leader in a political game wants their faction to win, for their own goals to succeed, and for their enemies to be crushed. This means that they can’t step in and encourage someone on the enemy team to speak up, and if they’re the best at debating on their team, why wouldn’t they just take center stage at all times? A mediator fulfills the functions of a PC leader – facilitating player empowerment, ensuring the game goes according to plan – while also keeping the playing field level and ensuring that the mechanics of the game still work. This mediator can be anyone – an emperor, the executor of a will, the commander of the military guiding the figures on the map – but in my opinion is an essential figure.

Another option is to build into the very mechanics of the game ways for every player to be involved. This could be how the political mechanisms work – there’s a senate who vote on issues and events cannot transpire without majority approval, for example – or it could be based on classes and magic. If every team has a unique way of approaching a problem, then they can feel special and involved even though they’re all doing similar things. I remember in one Frontier, I was the leader of a team of aliens who were covered in eyes. We had the special power that we could communicate with one another without other people hearing, and we’d do that constantly, discussing our plans and coming to a consensus together, which helped us feel like the agrarian populists we were. You should tailor the magic system of your game to fit with what a political game needs (something that is very, very different from what a normal adventure game requires!)

The fourth part of a good political game is very challenging, but solves one of the biggest problems a political game faces – having things to do in the game that isn’t just politicking. There’s a lot of ways to do this. You can give the characters intense emotional connections that move past the politics, or you could disrupt the politics with monsters, forcing the players to stand up and defend themselves. You could also have a game be non-political with political elements, where there’s a small group of people flowed to argue about politics in a room while everyone else runs around and plays a normal game. I don’t really know of a way to do this that both keeps the political game feeling secure without feeling a little ham-fisted, but finding a solution to how to do this will help the political game function.

The fourth part of a good political game is very challenging, but solves one of the biggest problems a political game faces – having things to do in the game that isn’t just politicking. There’s a lot of ways to do this. You can give the characters intense emotional connections that move past the politics, or you could disrupt the politics with monsters, forcing the players to stand up and defend themselves. You could also have a game be non-political with political elements, where there’s a small group of people flowed to argue about politics in a room while everyone else runs around and plays a normal game. I don’t really know of a way to do this that both keeps the political game feeling secure without feeling a little ham-fisted, but finding a solution to how to do this will help the political game function.

These are vital and cool things for a political game to have, and I would consider them baseline pieces of advice. Having all of these things will help ensure your game goes as smoothly as possible and are tried-and-true methods for keeping your game involved. However, all of these notes, while important, don’t actually solve the problems inherent in a political game. I’m going to propose some of my solutions, and touch on the question brought up by the previous paragraph – how do you make politics play nice with the rest of a game?

Consequences and “Mafioso Politics”

The first and biggest thing you can add to your political games to make them meaningful is consequences. This is especially easy in serial games – the actions of one game directly influence the outcome of the next game, and that means your choices really matter! You want to protect your people, because you know that if you don’t, they could be wiped off the face of the world. This is harder in a game that’s on its own, but there are solutions. One way I could imagine is that anyone who fails at becoming emperor are executed – you want to be emperor so you don’t die! Another way could be as simple as having a map in-game, and when places are wiped off the map, they are physically erased. Giving something as simple as a physical or event-based indicator of your choices doing things helps ground them in reality, and make it feel meaningful.

Another solution, which is honestly it’s own kind of game entirely, is what I call “Mafioso Politics”. In a mafioso political game, small groups have distinct goals which can mainly be achieved by negotiation, but! They all have knives. Something simple like that suddenly adds a new tone to the politics. You want to work together, because otherwise you’ll be stabbed! And vice versa, you have a sudden and powerful tool to get what you want if you need to, by stabbing your enemy. I’ve run two mafioso political games, both at Frontiers (although I suspect it’s only a matter of time before I run one at an Advanced camp), Partition City and Monsoon City, it’s spiritual successor. Both games were, at their core, political games, but they were also set at a market with plenty of other things happening, and disagreements were settled with knives and violence in addition to words and subtle discussions. Perhaps the strongest thing Partition City did to pull its weight as a political game was the use of rumors. Everyone had 3-5 rumors about their character as their character sheet, and they had full liberty to choose which rumors were true and by how much. Other characters could buy rumors as part of the point-buy system, and then use those rumors in-game. A couple of players spent the whole game trying to collect as many rumors as possible, and use them against people. This was a cool way for politics to be relevant and play a role, without feeling like people had to sit around a table and argue.

These are obviously just a couple of solutions to the political game problem. If you’re going to write a political game, you need to seriously think about the problems I’ve outlined, but once you think you’ve conquered them, your game is going to be amazing. Now that we’ve gone over what a political game is, some of the problems with a political game, and some of the solutions, we can talk about something which a number of people requested – flow! How do you write the flow for a political game?

The Flow of Politics

Even though political games tend to have very loose flow, understanding how that flow fits together will make your political games shine. If your game only has minor political elements, it should still make use of this simple structure to make sure things stay interesting for the political aspects. This flow has a simple structure, and it’s easy to add other parts to it in order to make it function better. I’m not quite sure what diamond flow would look like for a political game, but integrating those two structures could work really well! I could also imagine including a “final battle” or something similar.

Even though political games tend to have very loose flow, understanding how that flow fits together will make your political games shine. If your game only has minor political elements, it should still make use of this simple structure to make sure things stay interesting for the political aspects. This flow has a simple structure, and it’s easy to add other parts to it in order to make it function better. I’m not quite sure what diamond flow would look like for a political game, but integrating those two structures could work really well! I could also imagine including a “final battle” or something similar.

The political game begins with Act 1: the Introduction. In the introduction, everyone meets each other, hands are shaken, and the basic structure of the game is established. It’s always important to have time for this, so people can understand how the game ticks and get comfortable with the structure. If you imagine playing a political game to be like playing a board game, you’re going to want people to be familiar with the rules and be used to it before the exciting things happen!

The next act is Act 2: the Twist(s)! Even though I compared playing a political game to being like playing a board game earlier, the reality is that you don’t want to be “just” playing a game – you want excitement! Intrigue! Everything fun! In light of that, something really weird should happen about halfway through game. Maybe the king dies, or one of the leading political figures reveals themself to be an alien, or maybe a barbarian horde invades – whatever it is, it should change the landscape of the politics without putting an end to the politics themselves. One twist can often be enough for a smaller game, but a bigger game can always benefit from more and more complex twists. Just make sure they’re staggered carefully – having too many twists at once will lead to information overload.

The final act is Act 3: the Conclusion. Players should be aware that the end of the game is fast approaching, and be able to act with that knowledge. The new king is crowned, the UN implements a plan, the space constitution is written. Game reaches a satisfactory ending, and people are able to understand whether their schemes have failed or succeeded. It is vital that, despite all the conflict and disagreement over the course of the game that has occurred, there is still something that wraps it up. People need and want a satisfying conclusion, and it’s important that your political game is able to provide that.

There are two forces acting within a political game, defining the tension of the flow. On one hand, you want your political game to be like a board game (as established in act 1), with consistent rules that people can understand and take advantage of in order to “win”. On the other hand, you want the game to have room for change and excitement, and not to become dull and repetitive. Striking this balance is one of the most fun parts of writing a political game, as you establish how people can have fun as characters but also as players. The fact that we call them adventure “games” underlines how important it is for the game to have fun built into the mechanics of the game. In political games, this is more important than in any other form of game. Gives you something to think about!

And Now the Rains Weep O’er his Hall

Well that’s it everyone! I hope this article was able to inspire you with your next big endeavor, and even if you’re not writing a political game, that it was able to teach you a fair bit about what games need to be functional and fun for everyone. Political games are my favorite kind of game to be a PC in, and it’s a real shame that we’ve stopped writing them as often as we used to. I hope this article can inspire you to find the Tyrion Lannister inside of you, and get ready to play the most dangerous game.

Well that’s it everyone! I hope this article was able to inspire you with your next big endeavor, and even if you’re not writing a political game, that it was able to teach you a fair bit about what games need to be functional and fun for everyone. Political games are my favorite kind of game to be a PC in, and it’s a real shame that we’ve stopped writing them as often as we used to. I hope this article can inspire you to find the Tyrion Lannister inside of you, and get ready to play the most dangerous game.

Written by Jay Dragon

Posted on 1/23/18

Environmental Storytelling

Environmental Storytelling

It’s tough to judge games. So much of it can be determined by where in the game you are, who you interact with, and what happens to you. Even if you don’t have fun, the staff involved in it are skilled at making it an enjoyable experience for the majority of people. Generally, you can feel whether a game went well or not (especially as you become a staff member), but if you asked me what the best five games I’d ever played was, I wouldn’t have a concrete answer. Game writing is a cumulative process which I’ve learned from playing games, reading articles on the Story Board tumblr about games, and talking about games (a lot!), and every single game contributes to that process. However! There are two games I’ve played over the past 6 years that I believe have introduced a completely new method of storytelling to Wayfinder Adventure Games, and have deeply and profoundly impacted my view on what can be done in an Adventure Game. These two games are A Hollow Egg Hatches Eyes by Zach and Penny Weber, and Out of the Frost by Kate Muste.

A Hollow Egg Hatches Eyes

A Hollow Egg Hatches Eyes is a very strange game. While perhaps it’s similar to games run in Wayfinder’s history (a subject I’m not an expert on), it is vastly different from what we think of in modern terms of gamewriting. It’s set in a small village on a small island (very similar to Edo-period Japan), where a group of British-inspired sailors have washed on shore and caused all sorts of mayhem. The bear they brought with them killed the guardian of the forest and ate its heart, transforming into the new guardian spirit and driving the spirit world of the island into disarray. Horrible diseases (including red string, black eyes, and smallpox) were ravaging the population, and only the spirit doctors could help the people of the village return harmony to nature. It was a game about community, interpersonal support, the magic of nature, and the feeling of something absolutely unknowable happening to you. Production made more than 30 tiny puppets and statues which represented the various minor spirits of the forest, and lit them up with glowsticks and LED lights, creating the illusion that the forest is full of teeming, glowing magic. The sound of tinkling chimes and rushing water played across the entire campus, creating the illusion of strange forces at work. And the flow and game mechanics were unlike anything we’ve done since.

An important game convention was the use of disease. Everyone had a metal water bottle with them that contained about a dozen small slips of paper, rolled up into balls. Whenever the bell in the main space would toll, everyone would pull a slip of paper out of their bottle, and gain the new symptom of the disease. This might mean drawing eyes on your knuckles, tracing a new red line across your skin, or acting like you’re slowly going blind. This was the main antagonistic conflict of the game, as players feared and were tortured by the strange magics that consumed them. While the spirit doctors could help, their resources were limited. It created an atmosphere of terror and desperation as everyone’s health slowly decayed.