Held With Hope!:

An Intro Game’s Flow

When I was younger, I was terrified of flow. When I’d write games, I’d desperately try to avoid thinking about flow. I’d build everything that I could first, and then awkwardly stitch together some scenes in a linear order in order to create a flow. I knew about the concept of Diamond Flow, certainly, but I didn’t really understand how to apply that to make a coherent story. And I know I’m not the only person who felt that way. When we’re in High School Lit, we read about the Hero’s Journey. The hero is chilling at home, when all of a sudden they are called to action, and must embark on an epic voyage, which leads them through much pain and trouble. At the end, they fulfill the call (or fail miserably trying) and try to return home, but things have changed, and nothing can quite be the same. While not all stories follow this structure, it’s true that there is a certain group of stories which adhere to this narrative style (especially in modern Western literature). Intro Games, in addition to the visual and setting similarities, also follow the same narrative structure. But story narratives are different from character narratives – in the Hero’s Journey there’s only one protagonist, but in an Intro Game there are fifty! How do we make this work?

When I was younger, I was terrified of flow. When I’d write games, I’d desperately try to avoid thinking about flow. I’d build everything that I could first, and then awkwardly stitch together some scenes in a linear order in order to create a flow. I knew about the concept of Diamond Flow, certainly, but I didn’t really understand how to apply that to make a coherent story. And I know I’m not the only person who felt that way. When we’re in High School Lit, we read about the Hero’s Journey. The hero is chilling at home, when all of a sudden they are called to action, and must embark on an epic voyage, which leads them through much pain and trouble. At the end, they fulfill the call (or fail miserably trying) and try to return home, but things have changed, and nothing can quite be the same. While not all stories follow this structure, it’s true that there is a certain group of stories which adhere to this narrative style (especially in modern Western literature). Intro Games, in addition to the visual and setting similarities, also follow the same narrative structure. But story narratives are different from character narratives – in the Hero’s Journey there’s only one protagonist, but in an Intro Game there are fifty! How do we make this work?

The Players’ Journey

We’re going to take the players on a journey. This journey won’t be individual, as players will be given plenty of chances to make their own stories and discover their own adventures. This journey won’t be paced the same every time – each Adventure Game would like the journey to focus more on different sections of the path. Not every game follows this journey – there are plenty of reasons as to why you’d want to change things up and mix it around. But this is a journey where every step follows the one before it very comfortably, and if you follow it, I promise you your game will at the very least make coherent sense and allow the players a sense of satisfaction.

So often we talk about Diamond Flow in Intro Games. In fact, that article I just linked to is required reading, in order to understand the rest of this article. It describes perfectly how to use Diamond Flow and how to use it well. However, it is a popular misconception that Diamond Flow is the core of an Intro Game. In fact, Diamond Flow is merely a tool you can use in order to make your narrative make sense. While it’s not the only tool available to a gamewriter (Jeremy Gleick and I used the “final battle” tool over and over again in The Horned King to great success), it is certainly the most reliable one for generating games that are the proper length of time and maximally empower players without spreading staff resources too thin.

You take your diamonds and you apply them to the journey, generally with some padding in between. You want two diamonds per game segment, generally, and an Intro Game at a day camp has two game segments. Diamonds fit into and augment the journey, helping to break it up into manageable pieces and helping it to feel less like a big mob of people walking from one location to another. Done smoothly, players will never even notice the journey is there. But what is the journey, and where does it begin?

The Beginning

Ah, the beginning. The PCs set up camp, explore the main space that Sets & Props has so lovingly built, and interact with each other in-character for the very first time. The Beginning is vital for making everyone feel at home in the world. They don’t know what craziness they have to look forward to until they know what it’s like to be normal. The Beginning doesn’t need to be long, just long enough that the players get to meet one another and establish some basic dynamics. The Beginning concludes with the players engaging in some kind of ritual or activity. The classic example is a wedding – the four teams from the four kingdoms arrive, shake hands, smile to one another, thank the gods that the evil necromancer isn’t here to spoil their fun, and commence with the wedding festivities under the watchful gaze of Grandmother Oak Tree.

Enter the Threat

Oh no! It’s the evil necromancer, with an army of Zooombies! The Big Bad and their monsters arrive on the scene, and disrupt whatever activity the players are engaged in. They chase the players away to a location which can be fortified against the monsters (the main space). This is how it looks when the Threat is being Active. When the Threat is more passive (for example, monsters devouring townsfolk near the wedding), then the players will come upon the Threat engaging in evil (hearing the screams and running to investigate), at which point the players will return to the main space of their free will (how do we fight off the monsters?). Either way, this introduces players to the Threat and sets the tone for their interactions with the Threat. A diamond can be inserted here by having the Threat be in multiple locations, and players have to split up to go deal with it.

Oh no! It’s the evil necromancer, with an army of Zooombies! The Big Bad and their monsters arrive on the scene, and disrupt whatever activity the players are engaged in. They chase the players away to a location which can be fortified against the monsters (the main space). This is how it looks when the Threat is being Active. When the Threat is more passive (for example, monsters devouring townsfolk near the wedding), then the players will come upon the Threat engaging in evil (hearing the screams and running to investigate), at which point the players will return to the main space of their free will (how do we fight off the monsters?). Either way, this introduces players to the Threat and sets the tone for their interactions with the Threat. A diamond can be inserted here by having the Threat be in multiple locations, and players have to split up to go deal with it.

The Messy Middle

So this is the part where you get to have fun. The general trajectory for this portion of the journey is that players will push back against the Threat, learn how to defeat the Threat, and acquire tools to defeat the Threat (be it internal or external). These three sub-parts, Pushing Back, Receiving Guidance, and Acquiring Tools can happen in any order, and some can happen multiple times throughout the middle. In some form, every step of flow in the middle of the game can be described as one of these three elements.

This is an excellent time to draw upon your Mission statements mentioned in the last article (you read the first part of this article, right?). What do the players do to accomplish Pushing Back? Well, perhaps they plan tactics, or cast cool spells, or one of your other Mission statements.

Seek Guidance

The players now must turn to some other force, in order to receive wisdom about how exactly to defeat this new Threat. Perhaps they call upon the spirit of Grandmother Oak Tree, or they consult the Book of Ancient Lore, or they discuss amongst themselves the best solution. This is intended to guide the PCs on what their next course of action is, and help them understand what exactly is going on. This is a good time to provide the PCs with an explanation, or prepare them for what’s coming next. A diamond can be inserted here by having each team seek advice from a different individual or source, and come back together to combine that information.

Obtain Tools

We’re not strong enough to defeat the Threat on our own. If we were, we would’ve defeated it the moment it arrived, way back in Part 2. The players are going to need to craft artifacts, prepare spells, or go forth and acquire relics in order to muster the strength to actually defeat the Threat. To do this, the players will need Tools and probably seek more Guidance. These tools are magical enchantments on their blades that let them kill the monsters, or a ritual which remotely disables the Emperor’s arcane shields. They are objects or actions which allow the players to actually be able to defeat the monsters, not just fight them. The guidance of this part is the instruction on how to use and apply these tools. A diamond can be included here by having the players acquire tools from multiple locations, or have to work together by combining discrete objects in separate rituals (The soldiers enchant their blades, the healers study under their god, the wizards learn a new spell, and the thieves sneak in and steal the necromancer’s phylactery).

We’re not strong enough to defeat the Threat on our own. If we were, we would’ve defeated it the moment it arrived, way back in Part 2. The players are going to need to craft artifacts, prepare spells, or go forth and acquire relics in order to muster the strength to actually defeat the Threat. To do this, the players will need Tools and probably seek more Guidance. These tools are magical enchantments on their blades that let them kill the monsters, or a ritual which remotely disables the Emperor’s arcane shields. They are objects or actions which allow the players to actually be able to defeat the monsters, not just fight them. The guidance of this part is the instruction on how to use and apply these tools. A diamond can be included here by having the players acquire tools from multiple locations, or have to work together by combining discrete objects in separate rituals (The soldiers enchant their blades, the healers study under their god, the wizards learn a new spell, and the thieves sneak in and steal the necromancer’s phylactery).

Push Back

The Players, having gained wisdom in order to fight against the Threat, now finally have the ability to stand up against it. This doesn’t mean they win, definitely not, but it means they have the chance to stand up for themselves and gain some ground. Sometimes this is literal, where the players literally push back the monsters, and sometimes it’s more metaphorical, where they win over neutral parties or take back sacred relics. A diamond can be included here by pushing the monsters back on several fronts, or for multiple confrontations.

Confront the Threat

Finally, the players are on an equal footing with the Threat. They can strike against evil, and defeat the darkness. Generally, this is the conclusion of the game, as the players march into the final battle, weapons drawn, and fight mano-a-mano with the monsters of nightmares. Once the Threat has been defeated (most often in a flurry of swords, although they can also be stopped with a ritual or the detonation of a bomb, for example), then the players get to celebrate and enjoy their freedom from evil. There’s already an excellent article on ending games written by Books, which can be found here. But wait! Is this truly the ending?

False Starts

This narrative journey is good in a long, sweeping fashion, and in vague terms if you follow it you’ll get a good game (which might lean a little on the short side). However, the real funkiness begins once you introduce hiccups in the plan. False Starts can occur at any point along this journey, as just when the PCs think they know what’s going on, an even bigger Threat appears! This Threat makes the previous Threat look totally unimportant, and now the PCs have to start all over in order to defeat it. The classic Intro Game with two game segments works with this – the players think they’re fighting the evil necromancer, when suddenly their goddess turns out to be trying to destroy them, and they have to spend the second half of game dealing with that. You can also use False Starts when the guidance fails to work, the tools don’t do as expected, or the PCs accidentally give the current Threat new powers. If there’s a plot twist in an Adventure game, generally that’s a False Start, and generally, False Starts are plot twists.

Tasks and Garnishes

As mentioned, you position Diamonds at various points throughout the Flow. Often, a common challenge in gamewriting is what exactly to have at all those diamond points. If you have three PC teams, and four diamonds, that’s twelve unique plot points you have to come up with! Don’t worry though, there’s a lot of tools available to you in order to adorn your Diamonds and make scenes interesting.

The first place to look when coming up with Tasks is to consult your Mission statements. Are there any that apply to making cool Tasks? If one of your Mission statements is “performing rituals”, perhaps squeeze some interesting different rituals in to accomplish tasks. This is the advantage of your Mission statements – they give you a way to identify what you want your flow points to be, and create a cohesive experience.

We also have a huge variety of “generic” tasks you can insert into your Flow, that we have used countless times over the years and can create cool and empowering scenes. Some of the classics include performing a ritual, solving a riddle, defeating a champion, performing a distraction, stealing an artifact, convincing a nobleperson, or fixing a device. An entire article could easily be written about all of these options and choices, so I’m not going to get into the details here. What you can do, is think about what tasks connect to your Mission statements, perhaps in unconventional ways. These tasks should involve a PC or multiple PCs performing a “verb” (fighting, solving, performing, building, etc) in a scene, with the support of an SPC (either a PC leader or a unique character). The Introduction to Flow article mentioned earlier goes into more detail regarding the purpose of these Flow points, and how to apply them within the narrative.

An Example

Here is a chart explaining the flow of Marathon Wakes (which can be found here, with flow under the document “Marathon Wakes”). This graph shows the entire flow, mapped out, with different colors indicating the six different parts of flow, and little explosions to mark major points of conflict. I encourage you to go along with the flow document and compare it to the notes I took.

Here is a chart explaining the flow of Marathon Wakes (which can be found here, with flow under the document “Marathon Wakes”). This graph shows the entire flow, mapped out, with different colors indicating the six different parts of flow, and little explosions to mark major points of conflict. I encourage you to go along with the flow document and compare it to the notes I took.

This is both one of the most straightforward and also one of the best Intro Game flows I’ve ever seen, and critically examining it has only made me more confident in that. The only deviation from what I’ve outlined above is the use of only one diamond in the first segment, however this is cleverly intentional. You’ll notice that there’s four significant points of conflict in the first game segment – this allows the game to continue and make sense time-wise without creating unnecessary distractions before Jeriko (the Big Bad) arrives. There’s also a cool scene at the beginning where each team has to present someone who is worthy, which creates drama and empowerment without violence or diamonds.

What’s also important to note about this game, is the lack of False Starts. While False Starts are useful in creating a twist halfway through the game, Marathon Wakes succeeds in making the plot stretch out by devoting a ton of time to the Beginning and a full two scenes to the Threat’s entrance. By dragging out the entrance, the players are given time to become very scared of Jeriko, and once Jeriko takes away the figure they thought was going to be the Big Good (Torrus), the players are shaken and totally disoriented.

Once the action starts, it’s really, really going, and the remaining four parts of game are all pushed through in the second game segment. However, nothing feels rushed – each part has its own space to breathe and is clearly marked out. The discovery of hope, that they do in fact have some way to kill Jeriko and that they can The first game segment is a slow burn, and while it ends on an “uplifting” note, that’s directly counter to the desolation the players have suffered. Meanwhile, the second game segment ends in a frenzied chaos, followed by a moment of pure celebration. The kids love it when one of them gets to become something special.

Once the action starts, it’s really, really going, and the remaining four parts of game are all pushed through in the second game segment. However, nothing feels rushed – each part has its own space to breathe and is clearly marked out. The discovery of hope, that they do in fact have some way to kill Jeriko and that they can The first game segment is a slow burn, and while it ends on an “uplifting” note, that’s directly counter to the desolation the players have suffered. Meanwhile, the second game segment ends in a frenzied chaos, followed by a moment of pure celebration. The kids love it when one of them gets to become something special.

The End of the Journey

So, that’s a very unexpected way to talk about flow. It’s certainly not conventional, and it’s also not applicable for every game! This isn’t intended to provide a comprehensive way to talk about all games, this is specifically intended for Intro Games and making Diamond Flow into a narrative arc, not just a tool for making flow longer. Thanks for coming with me on this journey, and I hope you learned a lot about how to tackle one of the most exciting parts of writing an Adventure Game.

By Jay Dragon

Jan. 2nd 2018

Gameplay and story are two very different things. The story is like a bird’s eye view of the entire game: it covers the themes and the aesthetic and the mission statement, as well as the plot at large. The gameplay is on the ground: the things that the players are actually experiencing and doing from moment to moment – the individual flow points. If the story is like looking at a forest, the gameplay is looking at each tree and seeing how it aligns with the rest.

Gameplay and story are two very different things. The story is like a bird’s eye view of the entire game: it covers the themes and the aesthetic and the mission statement, as well as the plot at large. The gameplay is on the ground: the things that the players are actually experiencing and doing from moment to moment – the individual flow points. If the story is like looking at a forest, the gameplay is looking at each tree and seeing how it aligns with the rest. The reason this is an exercise and not something you can use for every adventure game is that some verbs just aren’t good fits. We write games for our players, so when we come up with the verbs that we’re actually going to use for our game, there are a few extra things we need to consider. These can be broken down into three main categories:

The reason this is an exercise and not something you can use for every adventure game is that some verbs just aren’t good fits. We write games for our players, so when we come up with the verbs that we’re actually going to use for our game, there are a few extra things we need to consider. These can be broken down into three main categories:  In a game I ran back in 2022 called Tales of Anywhere, I had a series of flow points where the PCs needed to retrieve powerful relics from the gods of the world. While I could’ve just used the verb “Get” for all of those flow points, that would’ve meant having players do a really similar thing three times in a row. Instead, the verbs I used for those scenes were

In a game I ran back in 2022 called Tales of Anywhere, I had a series of flow points where the PCs needed to retrieve powerful relics from the gods of the world. While I could’ve just used the verb “Get” for all of those flow points, that would’ve meant having players do a really similar thing three times in a row. Instead, the verbs I used for those scenes were  Verbs are an incredibly useful tool to have in your toolbox, and they’re big all over the world of game design for a very good reason. Even if you never end up using the exercise or breaking down your previous flow points, understanding that the core of your game is player action can help you hone in on what will make your game genuinely fun to play. The point of verbs is to remember that the game, at its core, is all about what the players are doing – you can make the most beautiful sets and the best story ever, but at the end of the day, the players will experience what they

Verbs are an incredibly useful tool to have in your toolbox, and they’re big all over the world of game design for a very good reason. Even if you never end up using the exercise or breaking down your previous flow points, understanding that the core of your game is player action can help you hone in on what will make your game genuinely fun to play. The point of verbs is to remember that the game, at its core, is all about what the players are doing – you can make the most beautiful sets and the best story ever, but at the end of the day, the players will experience what they  We play Adventure Games because we want a specific experience. We want to cry, we want to laugh, we want to look cool, we want to hit stuff with foam sticks. From filling out a character survey to the final moments of game, you as a player are tailoring your character and your portrayal of them to achieve these ends. This tailoring is often called steering- you steer your character’s actions to suit what you want to get out of the game. Steering is pretty intuitive to most players, it’s more defined terminology to say that you, the player, are in control of your character. (This is the sort of revolutionary idea you come across reading larp theory.) What’s helpful about recognizing that steering exists is that it makes you more likely to use it to your advantage, and better optimize your character’s actions to get what you want. Recently we’ve been talking about making out-of-game goals alongside character creation. Steering is the tool you use to achieve those goals.

We play Adventure Games because we want a specific experience. We want to cry, we want to laugh, we want to look cool, we want to hit stuff with foam sticks. From filling out a character survey to the final moments of game, you as a player are tailoring your character and your portrayal of them to achieve these ends. This tailoring is often called steering- you steer your character’s actions to suit what you want to get out of the game. Steering is pretty intuitive to most players, it’s more defined terminology to say that you, the player, are in control of your character. (This is the sort of revolutionary idea you come across reading larp theory.) What’s helpful about recognizing that steering exists is that it makes you more likely to use it to your advantage, and better optimize your character’s actions to get what you want. Recently we’ve been talking about making out-of-game goals alongside character creation. Steering is the tool you use to achieve those goals. One particular type of steering I find interesting is playing to lose, which is also conveniently exactly what it sounds like. I’ve had a lot of great scenes come out of playing to lose, like two rounds of the Oldest Game that I played in Brennan Lee Mulligan’s Grad School, run during Winter Game 2017. Allowing my character, Puck, to lose the first game led to a quest to seek revenge and win– only to lose another round of the Oldest Game in an even more epic and disgraceful fashion. Books and movies are no fun if everything goes right for the protagonist. Playing to lose gives your character those speed-bumps an author would normally give to their characters, and often makes for a more interesting, cathartic story. Playing to lose can also be a great way to make your scene partner look good, which is one of the key rules of improv and always a good way to make a great scene.

One particular type of steering I find interesting is playing to lose, which is also conveniently exactly what it sounds like. I’ve had a lot of great scenes come out of playing to lose, like two rounds of the Oldest Game that I played in Brennan Lee Mulligan’s Grad School, run during Winter Game 2017. Allowing my character, Puck, to lose the first game led to a quest to seek revenge and win– only to lose another round of the Oldest Game in an even more epic and disgraceful fashion. Books and movies are no fun if everything goes right for the protagonist. Playing to lose gives your character those speed-bumps an author would normally give to their characters, and often makes for a more interesting, cathartic story. Playing to lose can also be a great way to make your scene partner look good, which is one of the key rules of improv and always a good way to make a great scene. Steering is ultimately about achieving goals in game, and the Three Way model is one way to categorize how people achieve these goals. The Three Way model (a larp-specific adaptation of the Threefold model, which is used in general RPG theory) proposes that all play-styles fall loosely into three categories: gamist, dramatist, and immersionist. Gamist players play to win; they want to solve a riddle, they want to outsmart the villain, they want to stab the Big Bad even after it’s dead. Dramatist players are playing to tell a cool story, and often control their actions to fit into a traditional narrative with a nice satisfying ending. Immersionist players play because they want to be as true to the experience of their character and the world they’re playing in as possible- if their character would sit in a corner and cry, goddamnit they’re going to sit in that corner for as long as their character would.

Steering is ultimately about achieving goals in game, and the Three Way model is one way to categorize how people achieve these goals. The Three Way model (a larp-specific adaptation of the Threefold model, which is used in general RPG theory) proposes that all play-styles fall loosely into three categories: gamist, dramatist, and immersionist. Gamist players play to win; they want to solve a riddle, they want to outsmart the villain, they want to stab the Big Bad even after it’s dead. Dramatist players are playing to tell a cool story, and often control their actions to fit into a traditional narrative with a nice satisfying ending. Immersionist players play because they want to be as true to the experience of their character and the world they’re playing in as possible- if their character would sit in a corner and cry, goddamnit they’re going to sit in that corner for as long as their character would. Of course these three play styles, like gender and dark chocolate, exist on a spectrum, and the boundaries can often be blurry. I myself fall somewhere between dramatism and immersionism. This is something I think shows in Puck’s actions; playing to lose both was definitely dramatist, but the desire to seek revenge was a result of deep immersion. Overlap is normal, and blending these different styles can often be unintentional. Someone accustomed to winning cool battles and finding loopholes in the magic system (typically a gamist perspective) when confronted with no fighting or magic can quickly become an adept narrative player, since the way to “win” that sort of scenario is to tell the coolest story. In a similar vein, playing for immersion can also get competitive, with some players bragging about bleed and overflowing emotions. These different type of players also often use the same mechanics. For example, steering can be used for both gamist and dramatist purposes, though is often frowned upon in cultures that put a high value on immersion. These elements can also easily co-exist in the same game, depending on whether there’s a tavern scene or a big battle or a mass ritual. It’s best to think of the distinctions of the Three Way model as ideas to play with rather than strict rules to follow. As the creator of the model, Petter Bøckmen, admitted, “Shoehorning everything into this model may lead to some really funny results.”

Of course these three play styles, like gender and dark chocolate, exist on a spectrum, and the boundaries can often be blurry. I myself fall somewhere between dramatism and immersionism. This is something I think shows in Puck’s actions; playing to lose both was definitely dramatist, but the desire to seek revenge was a result of deep immersion. Overlap is normal, and blending these different styles can often be unintentional. Someone accustomed to winning cool battles and finding loopholes in the magic system (typically a gamist perspective) when confronted with no fighting or magic can quickly become an adept narrative player, since the way to “win” that sort of scenario is to tell the coolest story. In a similar vein, playing for immersion can also get competitive, with some players bragging about bleed and overflowing emotions. These different type of players also often use the same mechanics. For example, steering can be used for both gamist and dramatist purposes, though is often frowned upon in cultures that put a high value on immersion. These elements can also easily co-exist in the same game, depending on whether there’s a tavern scene or a big battle or a mass ritual. It’s best to think of the distinctions of the Three Way model as ideas to play with rather than strict rules to follow. As the creator of the model, Petter Bøckmen, admitted, “Shoehorning everything into this model may lead to some really funny results.” Whether you were aware of all this theoretical jibber-jabber before or not, you have already used your intuition as a player to tailor your play style to different scenarios. You wouldn’t play a comedy game with the high dramatic style you might use in a fantasy game, and you probably wouldn’t put on a Texan accent in a fae court. The ideas behind steering and the Three Way Model are all similar ways to change how you play. They’re not set in stone, and one is certainly not better than the other, just different. What my hope is, with this knowledge in hand, you will try something new in the next game you play, and maybe learn more about yourself and this delightful artform we all create together.

Whether you were aware of all this theoretical jibber-jabber before or not, you have already used your intuition as a player to tailor your play style to different scenarios. You wouldn’t play a comedy game with the high dramatic style you might use in a fantasy game, and you probably wouldn’t put on a Texan accent in a fae court. The ideas behind steering and the Three Way Model are all similar ways to change how you play. They’re not set in stone, and one is certainly not better than the other, just different. What my hope is, with this knowledge in hand, you will try something new in the next game you play, and maybe learn more about yourself and this delightful artform we all create together. Game Mechanics are one of the most complicated aspects of writing an Adventure Game, and it’s not because of the difficulty. Every single game has mechanical elements, with different degrees of prominence within a particular game. These mechanics develop together into systems – relationships of mechanics that inform each other. For example, each different spell a wizard can know is a mechanic, together they form a system. As someone who is involved heavily in the Tabletop Roleplaying Game world, a world where systems are far more prominent when discussing game design, I find myself thinking a lot about how to use mechanics and systems to develop the emotional reactions I would like in a game. In this article, I’m not going to talk about how to use game mechanics for your game. Not yet. Instead, I’m going to introduce a vocabulary for talking about game mechanics, taking them apart, and examining them critically. None of these systems of mechanical discussion are perfect for every game mechanic. Instead, you should mix and match these different divisions of game mechanics to gain a deeper understanding of how game mechanics work.

Game Mechanics are one of the most complicated aspects of writing an Adventure Game, and it’s not because of the difficulty. Every single game has mechanical elements, with different degrees of prominence within a particular game. These mechanics develop together into systems – relationships of mechanics that inform each other. For example, each different spell a wizard can know is a mechanic, together they form a system. As someone who is involved heavily in the Tabletop Roleplaying Game world, a world where systems are far more prominent when discussing game design, I find myself thinking a lot about how to use mechanics and systems to develop the emotional reactions I would like in a game. In this article, I’m not going to talk about how to use game mechanics for your game. Not yet. Instead, I’m going to introduce a vocabulary for talking about game mechanics, taking them apart, and examining them critically. None of these systems of mechanical discussion are perfect for every game mechanic. Instead, you should mix and match these different divisions of game mechanics to gain a deeper understanding of how game mechanics work. That last point is the most important. Game mechanics naturally beget other game mechanics, as part of developing a system. We possess a death system, in which players understand what is to happen mechanically when they are killed as a result of actions in game. That is a game mechanic. As an extension of that, there must be game mechanics in place to facilitate what happens ways to die. Do I die if someone points at me and says “Death!”. Do I die if someone hits me with a sword or shoots me with a NERF bullet? Do I die if someone shines a red light on me? What if something weird happens, like I set off a tripwire? These are all game mechanics that combine with the mechanism of RE to create a game system.

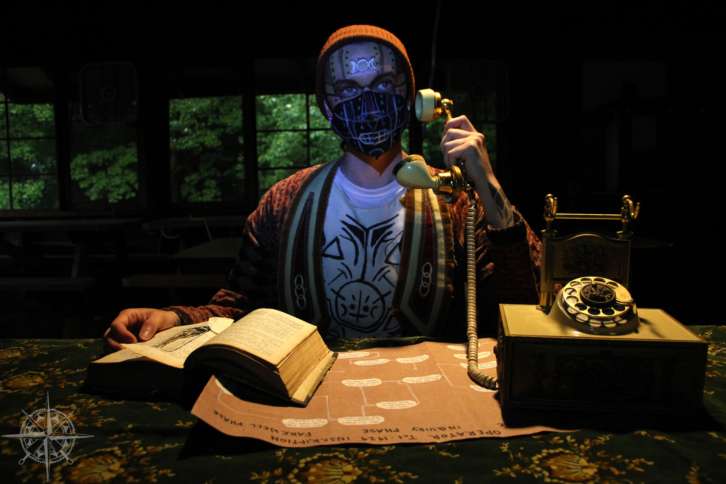

That last point is the most important. Game mechanics naturally beget other game mechanics, as part of developing a system. We possess a death system, in which players understand what is to happen mechanically when they are killed as a result of actions in game. That is a game mechanic. As an extension of that, there must be game mechanics in place to facilitate what happens ways to die. Do I die if someone points at me and says “Death!”. Do I die if someone hits me with a sword or shoots me with a NERF bullet? Do I die if someone shines a red light on me? What if something weird happens, like I set off a tripwire? These are all game mechanics that combine with the mechanism of RE to create a game system. In that scenario, a common solution is to tie the withering to a visual cue. I might, before game, inform everyone that if they see Jud Packard, that means their skin begins to rot off. Sometimes, this works! However, visual cues don’t often work passively. It’s easy to forget that there’s something special associated with Jud Packard, in the heat of the moment. The best way to ensure players remember visual cues is by making the visual cue impossible to miss and to really, really drill it into their heads. Silence Blooming, a game ran in 2017 by myself and Jeremy Gleick, made heavy use of visual cues for game mechanics. The one that really stuck in people’s heads was “Everyone follow the Whale Monster!” which is to say, that when people see a giant monster composed of multiple moving people, they have to follow it. We turned this into a callback to ensure that people would remember it, and it worked effectively in game. We also made strong use of colored lights for verbal cues. I was wrapped entirely in glowing string lights for game, and if you had a particular disease, you had to follow me. This only mattered to people with the disease, so people were already aware of something to look out for. Also, string lights are very visible at night.

In that scenario, a common solution is to tie the withering to a visual cue. I might, before game, inform everyone that if they see Jud Packard, that means their skin begins to rot off. Sometimes, this works! However, visual cues don’t often work passively. It’s easy to forget that there’s something special associated with Jud Packard, in the heat of the moment. The best way to ensure players remember visual cues is by making the visual cue impossible to miss and to really, really drill it into their heads. Silence Blooming, a game ran in 2017 by myself and Jeremy Gleick, made heavy use of visual cues for game mechanics. The one that really stuck in people’s heads was “Everyone follow the Whale Monster!” which is to say, that when people see a giant monster composed of multiple moving people, they have to follow it. We turned this into a callback to ensure that people would remember it, and it worked effectively in game. We also made strong use of colored lights for verbal cues. I was wrapped entirely in glowing string lights for game, and if you had a particular disease, you had to follow me. This only mattered to people with the disease, so people were already aware of something to look out for. Also, string lights are very visible at night. In Art History (my personal discipline) there is a continuum that exists, between naturalism (that is, art that perfectly resembles the real world) and symbolic (art that has no visual connection to the natural world). We can also construct this line for game mechanics. This section of this article draws on the work of Lauri Lukka in “6 Levels of Substitution: The Behavioral Substitution Model”, published in The Knudepunkt 2015 Companion Book. (An aside: if you ever have a free night or two, hunt down all the Knutpunkt/Knudepunkt/Solmukohta articles you can find, and check them out. There are some real gems!)

In Art History (my personal discipline) there is a continuum that exists, between naturalism (that is, art that perfectly resembles the real world) and symbolic (art that has no visual connection to the natural world). We can also construct this line for game mechanics. This section of this article draws on the work of Lauri Lukka in “6 Levels of Substitution: The Behavioral Substitution Model”, published in The Knudepunkt 2015 Companion Book. (An aside: if you ever have a free night or two, hunt down all the Knutpunkt/Knudepunkt/Solmukohta articles you can find, and check them out. There are some real gems!) In the middle are game mechanics which either depend more heavily on naturalistic behavior, or on symbolic information. Our system for sword combat, where we have abstracted it to the point where we’re not using literal swords, and we treat the swords differently than how they are as actual objects, but we strive for realism in how the swords operate, is a mostly-naturalistic mechanic. A system in which, instead of fighting with swords, you engage in a dance party, is heavily abstracted but in an interesting way. It’s still satisfying the same physical mechanisms as a sword fight does, but the swords have been abstracted out of the combat. Even further abstracted would be a system where sword fights are represented through a game of poker. Gone is the physical association, and instead is a mental association. One could say that a game of Texas Hold’em is a lot like a Mexican Standoff in terms of the tenseness and cultural associations, making a symbolic switch like that appealing.

In the middle are game mechanics which either depend more heavily on naturalistic behavior, or on symbolic information. Our system for sword combat, where we have abstracted it to the point where we’re not using literal swords, and we treat the swords differently than how they are as actual objects, but we strive for realism in how the swords operate, is a mostly-naturalistic mechanic. A system in which, instead of fighting with swords, you engage in a dance party, is heavily abstracted but in an interesting way. It’s still satisfying the same physical mechanisms as a sword fight does, but the swords have been abstracted out of the combat. Even further abstracted would be a system where sword fights are represented through a game of poker. Gone is the physical association, and instead is a mental association. One could say that a game of Texas Hold’em is a lot like a Mexican Standoff in terms of the tenseness and cultural associations, making a symbolic switch like that appealing. For the final portion of this article, we’re going to take a few game mechanics, and you must identify the cues of the mechanic, whether the mechanic is more naturalistic or symbolic, and whether the mechanic is active, passive, reactive, or collaborative. In addition, each mechanic has a different flaw with it that will cause problems during game, and I’d like you to identify how this appears. This isn’t a test – I don’t expect you to guess them perfectly. Instead, I want you to start using these different division systems as a way of talking about mechanics, and understand how they can be applied, and how they can be useful. If you disagree with me on any of these mechanics, you’re welcome to hunt me down on the internet and passionately explain to me why I’m wrong.

For the final portion of this article, we’re going to take a few game mechanics, and you must identify the cues of the mechanic, whether the mechanic is more naturalistic or symbolic, and whether the mechanic is active, passive, reactive, or collaborative. In addition, each mechanic has a different flaw with it that will cause problems during game, and I’d like you to identify how this appears. This isn’t a test – I don’t expect you to guess them perfectly. Instead, I want you to start using these different division systems as a way of talking about mechanics, and understand how they can be applied, and how they can be useful. If you disagree with me on any of these mechanics, you’re welcome to hunt me down on the internet and passionately explain to me why I’m wrong. 1. The Sword of Angrathnar. This is a visual object cue (the sword is an object, and it’s glowing red, which reminds you visually). This is not especially symbolic or naturalistic, as it abstracts a non-natural experience, but I could hear arguments leaning either way. It is an active game mechanic, as the wielder of the weapon inflicts it onto other players with the blade itself. The flaw that I would articulate is that the mechanic is too active – it takes control and limits the victim’s games in a way that isn’t fun (they now have to be ghosts forever, and don’t get to make their own choices while being invisible to everyone).

1. The Sword of Angrathnar. This is a visual object cue (the sword is an object, and it’s glowing red, which reminds you visually). This is not especially symbolic or naturalistic, as it abstracts a non-natural experience, but I could hear arguments leaning either way. It is an active game mechanic, as the wielder of the weapon inflicts it onto other players with the blade itself. The flaw that I would articulate is that the mechanic is too active – it takes control and limits the victim’s games in a way that isn’t fun (they now have to be ghosts forever, and don’t get to make their own choices while being invisible to everyone). Game Mechanics are, on a fundamental level, how we interface with the fiction that is the Adventure Game. Every single thing you do in an adventure game is technically a game mechanic, and even something as simple as talking to someone else can have multiple meanings or purposes. Don’t treat your game mechanics like something extra, to toss on top of your game when you need some garnish. They’re the tools you use to immerse your players and build your narrative. Take command of your mechanics, and sculpt your world with them. In the future, I’ll be talking about how mechanics combine, and how that builds a system.

Game Mechanics are, on a fundamental level, how we interface with the fiction that is the Adventure Game. Every single thing you do in an adventure game is technically a game mechanic, and even something as simple as talking to someone else can have multiple meanings or purposes. Don’t treat your game mechanics like something extra, to toss on top of your game when you need some garnish. They’re the tools you use to immerse your players and build your narrative. Take command of your mechanics, and sculpt your world with them. In the future, I’ll be talking about how mechanics combine, and how that builds a system. I’ll be completely honest – in my opinion, Game of Thrones is not a very good TV show. That doesn’t stop me from watching it (doing my best to avoid the constant misogyny and racism). The only actually enjoyable part of Game of Thrones is the political intrigue and power plays. Because boy are those a lot of fun! Watching people scheme against one another and forge (and break) powerful alliances in the name of their aspirations and deep-set character desires is great! Getting to be a mover and shaker in a situation like that one is an amazing example of meaningful choice – your actions have direct consequences for the entire world. Sometimes at Wayfinder we try to capture the experience of that situation in what we call “Political Games”. We’re not the only people to try that out – obviously other LARPs enjoy political settings, and you could easily argue that Model UN and Model Congress are perfect examples of political games (just without the roleplay). But, in my experience, it’s incredibly hard to write a good political game. In order to understand why, and how we can do better, we should take a look at what exactly a political game is and what it needs.

I’ll be completely honest – in my opinion, Game of Thrones is not a very good TV show. That doesn’t stop me from watching it (doing my best to avoid the constant misogyny and racism). The only actually enjoyable part of Game of Thrones is the political intrigue and power plays. Because boy are those a lot of fun! Watching people scheme against one another and forge (and break) powerful alliances in the name of their aspirations and deep-set character desires is great! Getting to be a mover and shaker in a situation like that one is an amazing example of meaningful choice – your actions have direct consequences for the entire world. Sometimes at Wayfinder we try to capture the experience of that situation in what we call “Political Games”. We’re not the only people to try that out – obviously other LARPs enjoy political settings, and you could easily argue that Model UN and Model Congress are perfect examples of political games (just without the roleplay). But, in my experience, it’s incredibly hard to write a good political game. In order to understand why, and how we can do better, we should take a look at what exactly a political game is and what it needs. A game in which individuals or small groups have very direct goals (free your people from slavery, shut down your enemy’s factories, get your plan to save the world approved by the UN)

A game in which individuals or small groups have very direct goals (free your people from slavery, shut down your enemy’s factories, get your plan to save the world approved by the UN) The fundamentally most necessary thing for a political game is stuff. Information, secrets, rumors, factoids, legal documents, the whole nine yards. This creates an immersive environment, as people now have tools they can fall back on to prove their points and engage in intrigue. In most games, we enjoy being able to make things up as we go along (improv!) but in political games, it’s good to have a framework that gives people a solid benchmark for reality. It’s best if this stuff can have a physical form in game – people can’t hold all the information they need in their heads at once. Writing all of this stuff is a lot of work, however. If you’re comfortable with that (like me) you’ll do strong, but if you’re not, you’re going to need another solution. That’s okay! I bet you can come up with a lot of creative solutions that will all accomplish the same thing – giving people tools in game that they can use to feel like the setting around them is real and that their actions will have meaningful impact.

The fundamentally most necessary thing for a political game is stuff. Information, secrets, rumors, factoids, legal documents, the whole nine yards. This creates an immersive environment, as people now have tools they can fall back on to prove their points and engage in intrigue. In most games, we enjoy being able to make things up as we go along (improv!) but in political games, it’s good to have a framework that gives people a solid benchmark for reality. It’s best if this stuff can have a physical form in game – people can’t hold all the information they need in their heads at once. Writing all of this stuff is a lot of work, however. If you’re comfortable with that (like me) you’ll do strong, but if you’re not, you’re going to need another solution. That’s okay! I bet you can come up with a lot of creative solutions that will all accomplish the same thing – giving people tools in game that they can use to feel like the setting around them is real and that their actions will have meaningful impact. The fourth part of a good political game is very challenging, but solves one of the biggest problems a political game faces – having things to do in the game that isn’t just politicking. There’s a lot of ways to do this. You can give the characters intense emotional connections that move past the politics, or you could disrupt the politics with monsters, forcing the players to stand up and defend themselves. You could also have a game be non-political with political elements, where there’s a small group of people flowed to argue about politics in a room while everyone else runs around and plays a normal game. I don’t really know of a way to do this that both keeps the political game feeling secure without feeling a little ham-fisted, but finding a solution to how to do this will help the political game function.

The fourth part of a good political game is very challenging, but solves one of the biggest problems a political game faces – having things to do in the game that isn’t just politicking. There’s a lot of ways to do this. You can give the characters intense emotional connections that move past the politics, or you could disrupt the politics with monsters, forcing the players to stand up and defend themselves. You could also have a game be non-political with political elements, where there’s a small group of people flowed to argue about politics in a room while everyone else runs around and plays a normal game. I don’t really know of a way to do this that both keeps the political game feeling secure without feeling a little ham-fisted, but finding a solution to how to do this will help the political game function. Even though political games tend to have very loose flow, understanding how that flow fits together will make your political games shine. If your game only has minor political elements, it should still make use of this simple structure to make sure things stay interesting for the political aspects. This flow has a simple structure, and it’s easy to add other parts to it in order to make it function better. I’m not quite sure what diamond flow would look like for a political game, but integrating those two structures could work really well! I could also imagine including a “final battle” or something similar.

Even though political games tend to have very loose flow, understanding how that flow fits together will make your political games shine. If your game only has minor political elements, it should still make use of this simple structure to make sure things stay interesting for the political aspects. This flow has a simple structure, and it’s easy to add other parts to it in order to make it function better. I’m not quite sure what diamond flow would look like for a political game, but integrating those two structures could work really well! I could also imagine including a “final battle” or something similar. Well that’s it everyone! I hope this article was able to inspire you with your next big endeavor, and even if you’re not writing a political game, that it was able to teach you a fair bit about what games need to be functional and fun for everyone. Political games are my favorite kind of game to be a PC in, and it’s a real shame that we’ve stopped writing them as often as we used to. I hope this article can inspire you to find the Tyrion Lannister inside of you, and get ready to play the most dangerous game.

Well that’s it everyone! I hope this article was able to inspire you with your next big endeavor, and even if you’re not writing a political game, that it was able to teach you a fair bit about what games need to be functional and fun for everyone. Political games are my favorite kind of game to be a PC in, and it’s a real shame that we’ve stopped writing them as often as we used to. I hope this article can inspire you to find the Tyrion Lannister inside of you, and get ready to play the most dangerous game.

What We Can Practice

What We Can Practice Late at night, JJ Muste and myself were staying up late after a Living Legend event I ran, and we were talking about horror games, and what makes them fun. We were bemoaning the lack of structure for how to write a horror game. JJ compared it to “a cake we keep making even though we don’t have a recipe. We just keep throwing eggs in and hoping it works!” While we’ve produced a number of really good horror games over the years, we’ve failed to come up with a common pattern between the games besides the fact that they’re scary, and I’ve played in one or two games that just failed to do anything for me. This article hopes to lay out a coherent structure for writing the flow of a horror game, and how to make that interesting for the players while keeping things scary. But first, before we can discuss that, we need to figure out what exactly a horror game is..

Late at night, JJ Muste and myself were staying up late after a Living Legend event I ran, and we were talking about horror games, and what makes them fun. We were bemoaning the lack of structure for how to write a horror game. JJ compared it to “a cake we keep making even though we don’t have a recipe. We just keep throwing eggs in and hoping it works!” While we’ve produced a number of really good horror games over the years, we’ve failed to come up with a common pattern between the games besides the fact that they’re scary, and I’ve played in one or two games that just failed to do anything for me. This article hopes to lay out a coherent structure for writing the flow of a horror game, and how to make that interesting for the players while keeping things scary. But first, before we can discuss that, we need to figure out what exactly a horror game is.. The Five Act Structure

The Five Act Structure Act 4: Looking for Help

Act 4: Looking for Help Boo!

Boo! Intro games are, far and away, the most common form of game we run at Wayfinder. Of our 14 unique games run in 2017, 9 of them were intro games, and 8 of them were held at day camps. If you want to get a game run, especially if you’ve never written a game before, the most surefire way statistically is to write an intro game for a day camp. They’re also the perfect way to get started writing games – they follow a comfortable formula and have a dedicated group of staff who spend an entire week, minimum, helping ensure your game runs well. So, knowing this, why is it that people don’t write more intro games?

Intro games are, far and away, the most common form of game we run at Wayfinder. Of our 14 unique games run in 2017, 9 of them were intro games, and 8 of them were held at day camps. If you want to get a game run, especially if you’ve never written a game before, the most surefire way statistically is to write an intro game for a day camp. They’re also the perfect way to get started writing games – they follow a comfortable formula and have a dedicated group of staff who spend an entire week, minimum, helping ensure your game runs well. So, knowing this, why is it that people don’t write more intro games? The core of any Intro Game (well, really any game at all), at least in my perspective, is the Premise. This is the beating heart of the game, the source from which you draw your power. Whenever you’re in doubt, whenever you feel unsure about where to go next, consult your premise and remember your roots. A premise is composed of multiple parts, which I’ll break down. Not all of these parts need to be clearly articulated – I know many gamewriters who don’t really care about all aspects of the premise, and in fact wouldn’t dream of writing any of this down. But, if you’re just beginning, it’s a good exercise to familiarize yourself with what you should be thinking about. Plus, this gives you a good time to get your creative juices stirring! The Premise is made up of four pieces – the Thesis, the Aesthetic, the Mission, and the Elevator Pitch. As you’re working on your game, every time you’re not sure where to go, you can always check back in on your Premise, and have that guide your choices. These shouldn’t dominate how you write your game – if you decide halfway through that your Thesis should be totally different, that’s great! This is your dream-baby. I just want to give you the tools to help guide your dream-baby, when you’re lost and don’t know where to go.

The core of any Intro Game (well, really any game at all), at least in my perspective, is the Premise. This is the beating heart of the game, the source from which you draw your power. Whenever you’re in doubt, whenever you feel unsure about where to go next, consult your premise and remember your roots. A premise is composed of multiple parts, which I’ll break down. Not all of these parts need to be clearly articulated – I know many gamewriters who don’t really care about all aspects of the premise, and in fact wouldn’t dream of writing any of this down. But, if you’re just beginning, it’s a good exercise to familiarize yourself with what you should be thinking about. Plus, this gives you a good time to get your creative juices stirring! The Premise is made up of four pieces – the Thesis, the Aesthetic, the Mission, and the Elevator Pitch. As you’re working on your game, every time you’re not sure where to go, you can always check back in on your Premise, and have that guide your choices. These shouldn’t dominate how you write your game – if you decide halfway through that your Thesis should be totally different, that’s great! This is your dream-baby. I just want to give you the tools to help guide your dream-baby, when you’re lost and don’t know where to go. In addition to establishing the Thesis of your game, you also want to develop a cohesive aesthetic. An aesthetic is “the set of principles underlying and guiding the work of a particular artist”. This refers to both the artistic vibes of your game, and the general mood of the adventure. When you talk about aesthetic in a movie like Mad Max: Fury Road, you’re talking about the color palette (oranges and blues), the appearance of the world (ramshackle cars, cobbled-together outfits, flamethrower guitars), and the landscape (bleak, inhospitable, without hope). In an adventure game, these things are reflected in the production lists and the world and group backgrounds

In addition to establishing the Thesis of your game, you also want to develop a cohesive aesthetic. An aesthetic is “the set of principles underlying and guiding the work of a particular artist”. This refers to both the artistic vibes of your game, and the general mood of the adventure. When you talk about aesthetic in a movie like Mad Max: Fury Road, you’re talking about the color palette (oranges and blues), the appearance of the world (ramshackle cars, cobbled-together outfits, flamethrower guitars), and the landscape (bleak, inhospitable, without hope). In an adventure game, these things are reflected in the production lists and the world and group backgrounds The next part of your Premise is the Mission of your game. This isn’t really something I’ve discussed with others before, and I think many people wouldn’t consider this even a part of game creation. However, I’ve found this is an essential part of designing other nerd activities, like Tabletop RPGs and video games.

The next part of your Premise is the Mission of your game. This isn’t really something I’ve discussed with others before, and I think many people wouldn’t consider this even a part of game creation. However, I’ve found this is an essential part of designing other nerd activities, like Tabletop RPGs and video games.